FLORENCE AND ROME

Leonardo da Vinci (1452‑1519) The new possibilities for drawing that were planted by Pisanello early in the fifteenth-century in Italy blossomed at the end of the century in the art of Leonardo da Vinci. More than any previous artist, Leonardo made drawing a means of discovery, creative stimulation, and invention. He drew with all the common media of his day—silverpoint, pen, and brush. He expanded the range of some media—charcoal and chalk. And he developed something new—pastel. (See Drawing Materials.) One of the most creative draftsmen of any period, Leonardo left posterity an enormous number of drawings, in sharp contrast to his few paintings. Including drawings bound in his notebooks, over 4000 survive.

3-1 Leonardo da Vinci, Drapery Study for a Seated Figure, ca. 1470-1475. Brush and gray tempera highlighted with white on a gray prepared canvas, 26.5 x 25.3 cm. Louvre Museum, Paris.

Leonardo studied with the Florentine sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio and remained in his workshop after his apprenticeship for several more years. As might be expected, the pupil absorbed the master’s manner of drawing. Giorgio Vasari writes that Leonardo specifically copied from Verrocchio “heads of women, beautiful in expression and in the adornment of the hair.” In addition, Leonardo absorbed from the older artist a number of distinct drawing skills. During the 1470s, Leonardo learned from Verrocchio to make drapery studies on fine linen in brush and ink and gouache in order to reproduce the fall and flow of cloth around the human body. The most celebrated of them, Drapery Study for a Seated Figure (figure 3-1), was one of nineteen exhibited at the Louvre museum in 1989.

Paradoxically, Leonardo’s approach was anything but naturalistic. The cloth to be studied was first moistened in wet clay, then arranged around a clay mannequin, and stiffened. In reality, the drapery studies are essays in modeling, the use of chiaroscuro to build solid form—the realm of the sculptor. Instead of hatching lines, smooth gradations made possible by a soft brush separate light from dark. The grand masses in Drapery Study for a Seated Figure emerge from darkness, and like many of the other drapery studies seem to glow in moonlight. The eerie highlights give no clue about the texture of the material. Leonardo subsequently began writing a treatise on chiaroscuro and the mysteries of light, subjects that became a hallmark of his art.

3-2 Leonardo da Vinci, Sketch for the Madonna of the Cat, ca. 1478-80. Pen and brown ink, stylus incised, 13.2 x 9.6 cm. The British Museum, London.

He also learned to make rapid sketches, as Verrocchio did when he captured the movement of animated children (figure 2-18). To sharpen the eye, Leonardo urged artists to keep a small sketchbook with them to note the infinite forms and positions of things. In many drawings, such as Sketch for the Madonna of the Cat (figure 3-2), Leonardo telescoped Verrocchio’s series, so to speak, into a single sketch that through vigorous pentimenti even more rapidly searched for suitable forms. The technique stimulated his imagination, as it brainstormed for new ideas. He urged artists to “rough out the arrangement of the limbs of your figures and first attend to the movements appropriate to the mental state of the creatures that make up your picture rather than to the beauty and perfection of their parts.” [Treatise on Painting] In the lower part of the design, his pen swirled in a tornado of possible positions for the Madonna’s legs. Even the tail of the cat seems to wag because Leonardo’s pen speculated about potential locations for it. By rapidly scribbling possibilities on top of each other, he let the process itself create his image.

3-3 Leonardo da Vinci, Study of a Young Woman’s Face, 1480s. Silverpoint, with traces of leadpoint, and white gouache highlights, on very pale ocher prepared paper, 18.1 x 15.9 cm.

Biblioteca Reale, Turin.

In the first two decades of his career, Leonardo used pen and metalpoint exclusively. On his earliest dated pen drawing, Landscape of the Arno River and Valley, unique in its vigorously scribbled horizontal hatching, he recorded the date, August 5, 1473. From 1478 to 1490 Leonardo preferred to use silverpoint and then abandoned it a few years later. (He never abandoned pen.) Three of his finest silverpoint drawings are the precisely detailed and highly finished profile head of a warrior (British Museum), the study of a woman’s hands on pink paper (Windsor 12558) that he made about 1478‑80 for the portrait he painted of Ginevra de’ Benci in the National Gallery, Washington, and the drawing he made six or eight years later, Study of a Young Woman’s Face (figure 3-3). Kenneth Clark called it “one of the most beautiful . . . in the world.” [Leonardo da Vinci, 94] Turning her head on her profiled shoulders, she glances sideways out of heavy, enlarged eyelids. Leonardo sketched the contours of her face with delicate parallel diagonal strokes, producing the smoky-soft transitions between light and dark for which his Mona Lisa is so famous. Longer and more broadly spaced hatching casts a veil of half-shadow over the back of her head, neck, and shoulders. Since Leonardo was left handed, his diagonal hatch marks proceed from lower right to upper left. Their regularity mimics a drypoint line. Long thought to be a study for the angel in the artist’s The Virgin of the Rocks, this silverpoint portrait wears a puzzling expression.

![3-4 Leonardo da Vinci, Studies of Nude or Draped Men, [for Adoration of Magi], 1481-83. Pen and brown ink over leadpoint, 27.7 x 20.9 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.](/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Leonardo3v-699x1024.jpg)

3-4 Leonardo da Vinci, Studies of Nude or Draped Men, [for Adoration of Magi], 1481-83. Pen and brown ink over leadpoint, 27.7 x 20.9 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Pen allowed Leonardo a freer and more experimental line, evident in Sketch for the Madonna of the Cat and in Studies of Nude or Draped Men. In them, he employed two alternate methods of invention, keeping his imagination fresh through the sketching process. He also freed his imagination by doodling. Scattered across his drawing sheets and notebook pages are dozens of heads, mostly in profile, sometimes of a handsome young man, but more often of an ugly old man. When his mind was wandering, something compelled Leonardo to repeat the latter image over and over again. Barely outlined or elaborately finished, these grotesque heads have an almost monotonous similarity. His grotesque heads were extensively copied, imitated, and reproduced, and for centuries they were Leonardo’s best-known drawings. Most of them look like the central figure in A Group of Five Grotesque Heads (figure 3-5), a famous and baffling pen drawing of the mid 1490s.

3-5 Leonardo da Vinci, A Group of Five Grotesque Heads, 1495. Pen and ink, 26.1 x 20.6 cm. Royal Library, Windsor.

The old man wearing a crown of oak leaves conforms to the stereotype: a creased forehead that bulges at the brow, a hooked nose that resembles a nutcracker, and a protruding lower lip and chin. The four ugly faces that surround him—especially the two laughing behind his back—seem to mock this stalwart and weathered old man. Leonardo derived this type of head from Roman coins, such as those of emperors Galba and Nero, and from the head of Verrocchio’s Colleoni. The fine diagonal lines of this pen drawing model the heads as though the technique were silverpoint.

Although Leonardo continued to draw in pen the rest of his life, after 1494 he preferred to draw in red or black chalk. Florentine artists began to use chalk in the 1480s, but mostly for cartoons rather than for studies. One exception, Luca Signorelli, did make studies in black chalk. Leonardo preceded other High Renaissance artists in exploiting the potential of chalk, its fluency and breadth, when he made hundreds of chalk studies for The Last Supper. He realized that the continuous modeling possible in chalk suited the new heroic style of the High Renaissance. Only seven drawings in chalk for The Last Supper still exist, including heads of the Apostles Philip, James, Bartholomew, and Judas (figure 3-6), who has the same features as the grotesque head wearing a crown of oak leaves.

3-6 Leonardo da Vinci, Judas, 1495-98. Red chalk on red ocher prepared paper, 18 x 15 cm. The Royal Collection, Windsor.

The renegade apostle turns away from the viewer in lost profile. The movement emphasizes the knotted muscles of his neck and helps reveal his mental state. Leonardo drew the head in red chalk on red paper to tone down contrasts and make subtle variations in the middle range of light and dark. In some places the hatching lines abandon a uniform diagonal direction and begin to follow the curvature of the form. In the black chalk drawing of the head of Philip on white paper, the softening of the shading is even greater because Leonardo probably blurred the soft chalk with his fingertips.

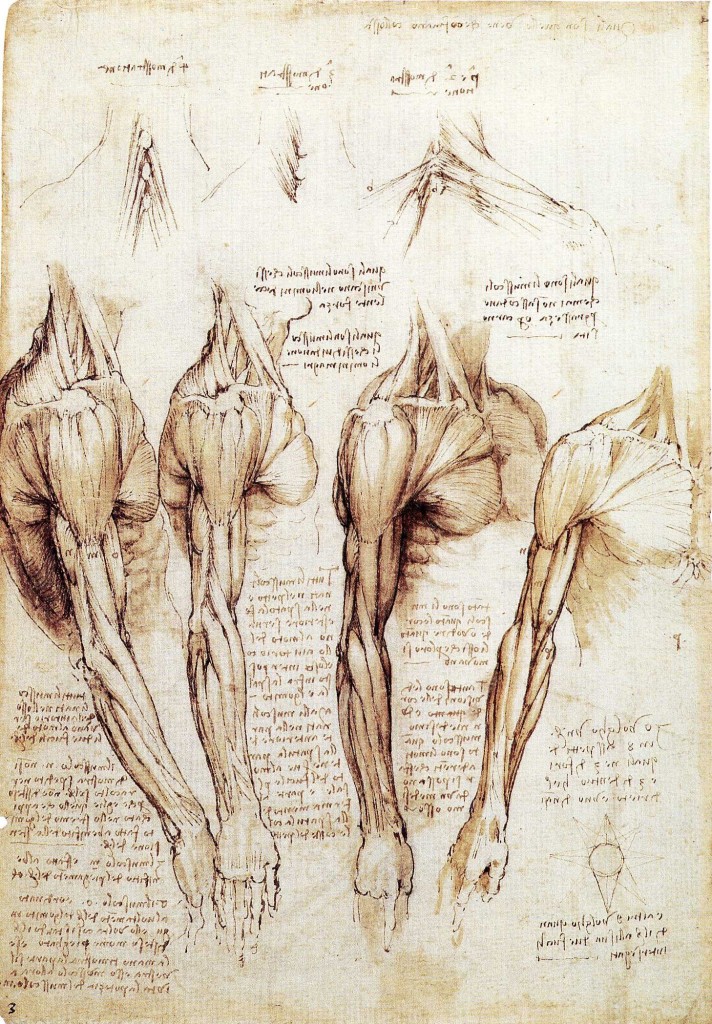

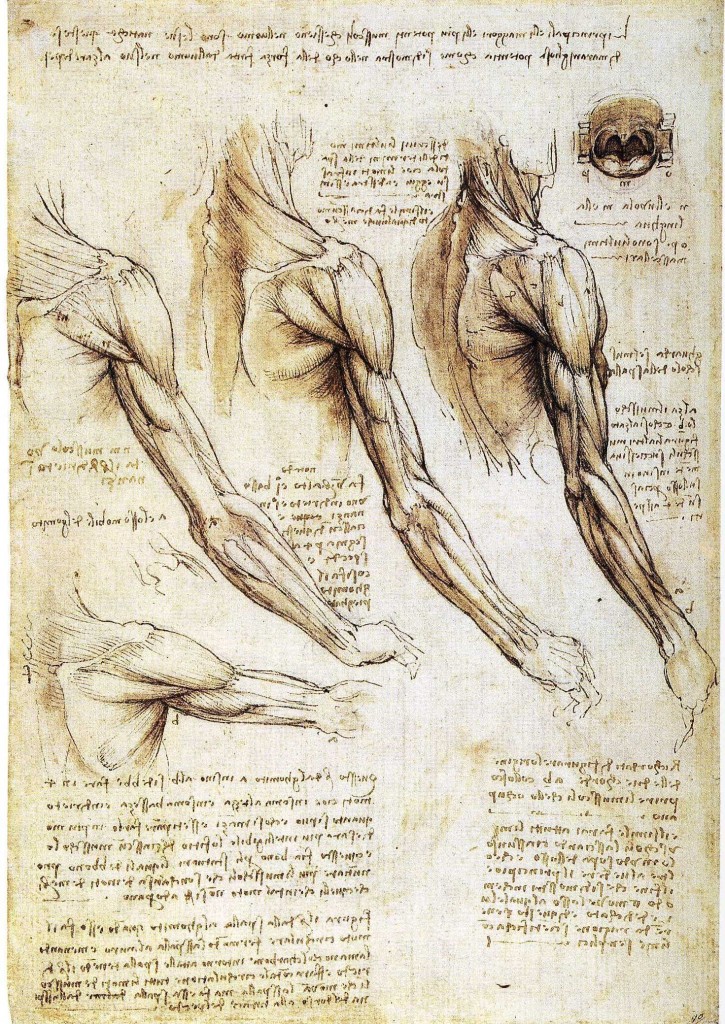

During his first stay in Milan Leonardo spent enormous energy on designs for a statue of a horse. He also began to keep notebooks filled with his studies of anatomy, botany, geology, architecture, and engineering. His earliest anatomical drawings date from 1488 to 1492. Ten years later he took up the study of anatomy again with greater energy in Florence, where he witnessed and practiced dissections. He may have been goaded by Michelangelo’s superior knowledge of anatomy at that time. Back in Milan, Leonardo, in collaboration with the physician Marcantonio della Torre of the University of Pavia, produced the most exquisite and precise anatomical drawings of his career, a group of drawings known as Windsor Anatomical Manuscript A. Leonardo often analyzed architecture, machines, or the human body from several views—front, back, and side, for example. In the two sheets Muscles of the Arm, Shoulder, and Neck (figure 3-7), he illustrated eight views of the same muscles by slowly rotating the body, as it were.

3-7 Leonardo da Vinci, Muscles of the Arm, Shoulder,and Neck, ca. 1510-1511. Left and right, pen and ink and wash, ca. 29 x 20 cm. Royal Library, Windsor.

How he would have loved to work with modern computer animation! The arm is outstretched at first, then moves down and back as the series continues. The anatomy pulsates with life. In Windsor Manuscript A, he finally showed the muscles and bones as they would be seen in the process of dissection, not according to some ancient or medieval theory. In these drawings he also invented “exploded” views in which he pulled pieces apart to distinguish them better. The Windsor anatomical drawings are always neat and legible. Fine parallel hatching, typical of engraving of the period, and a calculated application of wash occur on either side of muscle groups, an old method of modeling that clarifies the roundness of forms.

3-8 Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin and Child with St. Anne and John the Baptist (The Burlington House Cartoon), 1507-1508. Charcoal, soft black chalk, heightened with white on light brown tinted paper, 141.5 x 106 cm. National Gallery, London. [not in scale]

![3-9 Leonardo da Vinci, Horsemen and Foot Soldiers in Battle [for Battle of Anghiari], 1503-1506. Pen and ink over black chalk, 16.4 x 15.2 cm. Galleries dell'Accademia, Venice.](/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/3study2.jpg)

3-9 Leonardo da Vinci, Horsemen and Foot Soldiers in Battle [for Battle of Anghiari], 1503-1506. Pen and ink over black chalk, 16.4 x 15.2 cm. Galleries dell’Accademia, Venice.

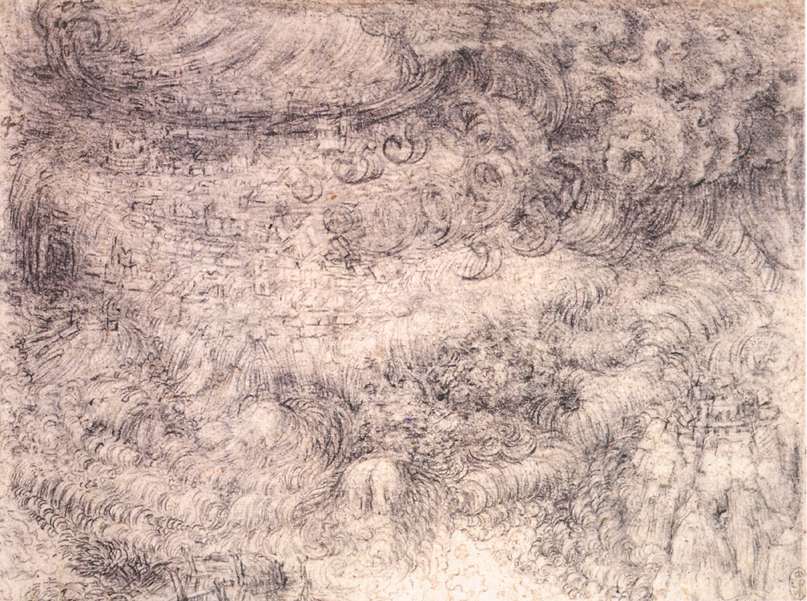

During his last period as a draftsman, before he left for France in 1517, Leonardo used red chalk less and less in favor of black chalk. Before this date, Leonardo made more horse studies for a second equestrian monument and a series of dreamy and enchanting black chalk drawings for masquerade costumes. Among his last extant drawings are black chalk drawings of stormy Alpine scenery, visible not far from Milan, and of a torrential deluge in the mountains. A Deluge (figure 3-10), one of a series of ten such drawings of similar dimensions at Windsor, illustrates a storm of such cyclonic force that it uproots mountains and crushes cities in its path. The drawing also illustrates the extensive descriptions of storms and a deluge written by Leonardo as advice for painters. His verbal descriptions insist on the organic nature of the scene: that everything—rain, wind, mountains, and valleys—be swept up in a vortex that continually crashes and eddies. Consequently, in the drawing he makes the lines of force visible in swirling clouds that show everything in flux. The explicit swirls derived from his study of the movement of water. Yet Leonardo’s vision goes far beyond a scientific study. The irresistible forces at work are on a tremendous scale and foretell a fearsome apocalypse.

Michelangelo (1475‑1564) In the second half of the fifteenth century, Florentine artists diligently drew the nude because of the role it played in the development of narrative art, or istoria, in which the actions of each figure help tell the story. Except for his architectural designs, Michelangelo made drawings of almost nothing but the male nude. Landscape and portraiture did not interest him. Not only did body language become the substance of his art, but also the male nude was for him the Platonic ideal of beauty itself.

3-11 Michelangelo, Three Figures, probably after Masaccio, ca. 1496. Pen and two hues of ink, 29.0 x 19.7 cm. Albertina, Vienna.

As far as we know, after the usual student exercises, Michelangelo never made silverpoint drawings. Perhaps he disliked the delicacy of the medium. From the start, Michelangelo used pen on plain paper. Except for a few early examples, he never drew on colored or prepared paper as many of his contemporaries did. Similarities of technique indicate that Michelangelo learned to use the pen from his master Ghirlandaio during his truncated apprenticeship with him in 1488‑89. Specifically, he learned to use cross‑hatching. He employed it in his earliest drawings, copies he made of works by Giotto and Masaccio (figure 3-11). Michelangelo was obviously attracted to the grandeur embodied in the figures of the earlier artists. Like Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo thickened the contours of his figures and sometimes added broadly spaced strokes alongside the figure—at the left, in this example—to suggest depth by the contrast of light and dark between the main figure and the background. The parallel lines of his hatching run in different directions, although along the back of the central figure the dark lines are as regular as those drawn with a ruler. Cross hatching appears rarely in Italian art before this time—Parri Spinelli (figure 2-15) is one exception—and may have been inspired by the prints of Schongauer, which Ghirlandaio and Michelangelo knew.

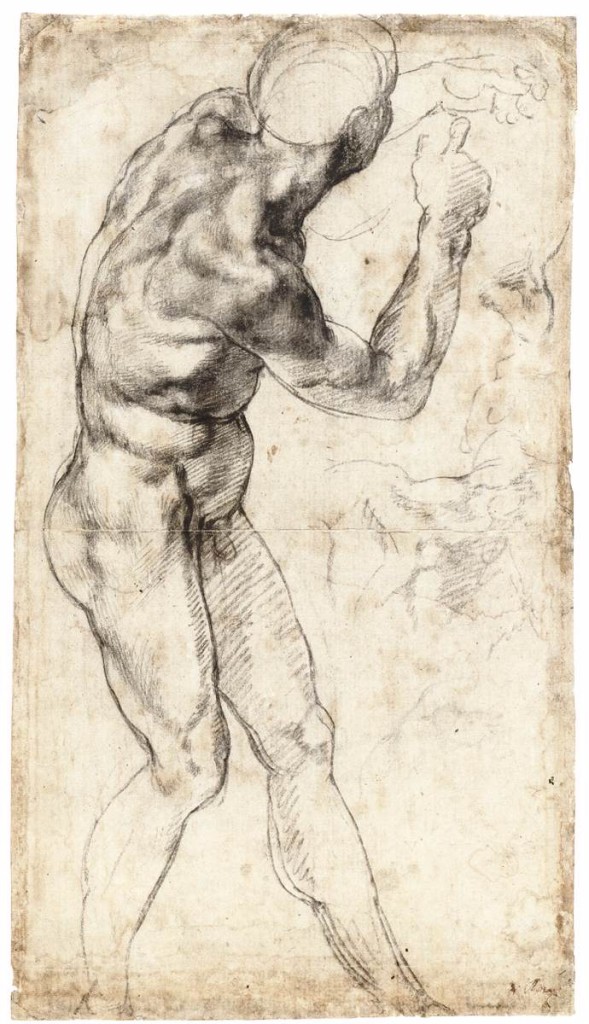

Michelangelo almost always drew in preparation for specific projects. In other words, each drawing immediately precedes the execution of a project. He seldom used an old drawing for a new project, and very few of his drawings were for practice. Another early pen drawing, A male Figure Seen from Behind (figure 3-12) was intended for The Battle of Cascina, a mural commissioned to match Leonardo da Vinci’s The Battle of Anghiari on a nearby wall.

3-12 Michelangelo, A Male Figure Seen from Behind (detail), ca. 1504. Pen and ink over some black chalk, 40.9 x 28.5 cm. Casa Buonarroti, Florence.

It is one of his few existing drawings based on a classical prototype, in this case a sarcophagus relief. Here Michelangelo adapted Ghirlandaio’s cross-hatched style to his own ends. The cross-hatched lines run every which way, and hatching covers the entire surface like a tatooing that envelops the entire body. It is sometimes said that in drawings like this Michelangelo worked his pen as though it were a claw‑toothed chisel cutting through marble. The similarity can be dismissed as a superficial resemblance, except that Michelangelo did use hatching to construct a relief map of the body rather than imitate the fall of light across it. There is no single source of light. Instead, the peaks of the anatomy are light and the valleys dark. In this sense, the paper became a slab of marble that he cut into with his pen, raising and lowering the surface.

Michelangelo adopted chalk after 1501, when he returned to Florence and began working alongside Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo’s earlier use of chalk no doubt influenced Michelangelo’s switch. By the 1520s he used black chalk almost exclusively. In his mural, Michelangelo chose to show Florentine soldiers scampering to meet the enemy after bathing nude in the river. He completed the cartoons for this central section, but their popularity with artists led to their destruction within a dozen years time.

3-13 Michelangelo, A Male Nude, ca. 1504. Black chalk with slight touches of white heightening, 40.4 x 22.4 cm. Teylers Museum, Haarlem.

Some of Michelangelo’s compositional studies for the mural survive, as do compositional drawings for The Last Judgment fresco. Such drawings tend to be nothing but clusters of figures without setting or framework. For several individual-figure studies for the Cascina project, such as A Male Nude (figure 3-13), he took up black chalk. Like the previously examined pen drawing (figure 3-12), Michelangelo retraced the chalk contour lines to make them emphatic. Chalk allowed him to modify and soften the network of hatching. The hatching is generally in a diagonal direction although occasionally it seems to follow the roundness of a form. Instead of cross hatching, he may have moistened and rubbed the chalk to create the line of deepest darks that runs down the man’s neck, shoulder, and side. There still does not seem to be a consistent light source: for example, highlights appear on the top of the arm, the bottom of the arm, and the middle of the forearm. Nevertheless, he has developed characteristics of a vigorous and animated figure style that will serve him well for decades.

While at work on the Sistine ceiling about five years later, Michelangelo made more and more studies in red chalk, especially for the second half of the ceiling. (By the time of The Last Judgment in 1534, he went back to black chalk almost exclusively.) Red chalk is more luminous and anticipated the brighter colors in the second half of the ceiling. In his drawings for the Sistine ceiling, he at times employed a stylus to incise a rough, preliminary underdrawing on a sheet, before going over his tentative explorations with chalk or pen. He must have made hundreds of drawings for the project, but only about sixty five remain. One of them, Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (figure 3-14), is rather carefully finished and includes the head, which Michelangelo usually worked on in a separate study.

3-14 Michelangelo, Studies for the Libyan Sibyl. 1511-1512. Red chalk, 28.9 x 21.4 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Sibyl reaches behind her because in the fresco she is picking up a book. Michelangelo ignored her legs because in the fresco they are covered. In the remaining space on the sheet, he restudied the left hand and left foot, visible beneath her gown, the points between which she pivots 180 degrees. Pentimenti reveal that the foreshortening of the arms gave him trouble. Here too, the diagonal crosshatching has been rubbed and blended along the arms and back for deeper and smoother contrasts of light and dark. In this drawing the lights and darks are more consistently arranged as from a single light source. Michelangelo sketched the torso again from a slightly different angle on the left, revealing that he began a drawing by blocking in major parts of the nude. The second sketch also reveals, by contrast, the degree to which he elaborated in the main nude figure.

Michelangelo more than likely made the drawing from a living male model after the composition had been decided upon and right before the cartoon was drawn. (Artists at this time almost never employed a female model.) If the realism in his drawing is taken literally, Michelangelo found someone with so little body fat that every muscle and sinew stands out. His broad shouldered nude is very different from the slender body types of the Quattrocento, whether by Pollaiuolo, Lippi, or even Leonardo before he left Florence. Michelangelo made the muscles and bones beneath the skin almost as prominent as in an ecorché, a mannequin with the skin removed. He altered the muscularity in the fresco painting, where it became more generalized, fleshier, perhaps one could say idealized. If he could so transform the anatomy from drawing to painting, no doubt Michelangelo could transform an ordinary-looking young model into this magnificent male physique. As he was drawing, he would have filtered what he saw through his memories of the Hellenistic art that he loved, especially the Belvedere Torso and Laocoon. The drawing, more than the painting, glorifies the beauty of the human body, which he believed was the acme of divine creation.

As he grew older, collectors besieged Michelangelo for a drawing, especially since papal patronage precluded his ever producing a painting or statue for them. Drawings had never been so highly regarded. Michelangelo rarely accepted a commission to supply a design—except for close friends—and never allowed a design of his reproduced in engraving. However, he often supplied his assistants, who were all notoriously mediocre artists, with model drawings for them to copy. He also made a few finished presentation drawings for Tommaso Cavalieri, Vittoria Colonna, and a few other friends. Mantegna and very likely Leonardo (a lost Neptune) had made similar gift drawings.

Vasari lists four drawing that Michelangelo presented to the decades-younger Roman aristocrat Cavalieri, for whom Michelangelo had deep affection. The drawings were the equivalent of the love poems that Michelangelo wrote to him and were circulating in Rome at the time. One presentation drawing, The Fall of Phaethon (figure 3-15), exists in three different vertical compositions. The version at Windsor, reproduced here, is highly finished. (Some other late drawings are quite vaporous in appearance.) The artist sharpened every outline and modeled the forms in such short strokes on grainy paper that the darks appear stippled. In the drawing, Zeus’s thunderbolt upends Phaeton, who now plummets into the Po River. He dared drive Apollo’s chariot of the sun and his downfall will turn Phaeton’s sisters into trees and his cousin into a swan. Michelangelo probably intended Ovid’s story about Phaeton to allegorize punishment for his hubris in passionately pursuing the divine.

As we have seen, Michelangelo made drawings at all stages of a project, from his first ideas, to compositional designs, figure studies, and cartoons. Also, surviving drawings come from every period of his long life. However, no drawings can be connected with two of his most popular works, the Pietà and the colossal David. Nevertheless, extant drawings can illustrate projects of his that were destroyed or were never completed—a bronze David or the original tomb for Julius II, for example.

Today, at most 600 sheets of drawing by Michelangelo remain—some of them worked on both sides. Scholars at one time or another have challenged the authenticity of most of them! Michelangelo himself ordered the destruction of some of his drawings. For example, in 1518 he instructed a friend to burn cartoons, probably those for the Sistine ceiling. Just before his death in 1564, he twice set fire to the drawings then in his studio, with the result that a smaller percentage of his late drawings have survived. Michelangelo frequently expressed concern that his work would be plagiarized, and he reportedly did not want anyone to see the effort he put into creating his work. On the contrary, he claimed that his art was the result of divine inspiration.

Raphael (1483‑1520) Raphael, the youngest of the three great High Renaissance draftsmen, arguably had more impact on the future of drawing than Leonardo or Michelangelo.

Raphael began his career in provincial Urbino, then moved to Perugia, where he became Perugino’s principle assistant. Most of the approximately fifty drawings from that early period (1499-1504) resemble those of his master. In Perugia, Raphael often used silverpoint for studies, and, unlike other major artists who abandoned silverpoint by the turn of the century, he continued to make drawings with it all his life.

3-16 Raphael, Study for the Norton Simon Madonna and Child, 1502-1503. Silverpoint on white prepared paper, 26.3 x 18.9 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille.

In a study for a painting of the Madonna and Child (figure 3-16), Raphael drew the contours of a workshop assistant (garzone) posed in a traditional formula for the subject. In the garzone drawing, he distilled the figure into simple, pure outlines with almost no internal modulation. His refined line scarcely articulated the anatomy of the peaceful young man. At the bottom of the sheet, he reconsidered the hand, tilting the book slightly and spreading the fingers to make its pose more languid. In a sketch like this, Raphael did not use drawing to experiment or discover, but to clarify.

In 1504 Raphael moved to Florence to spend some time studying. His “some time” stretched into four years, during which period he quickly absorbed the High Renaissance style of Fra Bartolommeo, Leonardo, and Michelangelo. In just those years, Leonardo and Michelangelo were drawing cartoons for The Battle of Anghiari and The Battle of Cascina, respectively.

3-17 Raphael, Five Studies of a Male Torso, 1504-08. Pen and ink over leadpoint underdrawing, 26.9 x 19.7 cm. British Museum, London.

In Florence, Raphael drew mostly in pen and soon developed speed, skill, and freedom in wielding it. Several drawings from this period, such as Five Studies of a Male Torso (figure, 3-17), were not made for specific projects and may once have belonged to a sketchbook. In this drawing, Raphael tried to make his own the torsions and muscular tensions of Michelangelo’s male nudes, although his figures do not have the broad shoulders and pumped up muscles of Michelangelo’s. Flexing his quill to create a variety of energetic dark lines and faint thin lines, Raphael strengthened contours with continuous dark lines around shoulders, arms, and torso. Light, occasional hatching and internal contours try to describe flexed and stretched muscles. However, they seem confined within, and separate from, the contours.

More than a sheet filled with random studies, it also betrays Raphael’s innate sense of rhythm. At the top, front and back versions of the same pose complement each other and, at the bottom, three variations of a twisting back thrust this way and that. The lessons Raphael learned from drawing the nude are evident in the energetic studies he made in preparation for a painting of The Entombment in 1507. Unlike Michelangelo, Raphael often used an early design in a later work: the figure in the center at the bottom of figure 3-17 reappears in the engraving The Massacre of Innocents at least a half dozen years later.

3-18 Raphael, Sketches of the Madonna and Child, Pen and ink over traces of red chalk, 25.3 x 18.3 cm. British Museum, London.

Inspired by Leonardo’s compositions of The Madonna and Child, Raphael concentrated on that subject in his Florentine period. In a number of rapidly sketched drawings, such as Sketches of the Madonna and Child (figure 3-18), he experimented with various arrangements of the motif. His calligraphic pen or chalk line circled around the forms until he found the right solution and then strengthened it. Many faint lines barely block out forms; other darker lines rework the pose of the lively Christ Child. Pentimenti are plentiful as Raphael “thinks out loud” on the paper. In short, he learned to explore and discover solutions to design problems through the process of drawing, as Leonard had done in Sketch for the Madonna of the Cat (figure 3-2). The contrast between Raphael’s pen drawings inspired by Michelangelo and Leonardo and his silverpoint garzone study from Perugia (figure 3-16) could not be greater.

From the start of his career in Perugia, Raphael followed an orderly process of drawing in the creation of a new painting. Typically, he began by making rough sketches, like fig. 3-18, to experiment, to capture inspiration, and to generate first ideas (primi pensieri). He then made a variety of sketches of groups to harmonize their actions and form a composition. Only then did he make studies from the nude model to clarify the anatomy of the pose of an individual or a group. He might also make separate draped studies. Ultimately, he put together all these studies in an elaborated modello (model) for the approval of the patron. Modelli were usually pen drawings in which the figural arrangements were unified and clarified with chiaroscuro washes. To transfer the design to a canvas or wall, Raphael next repeated it in a full-scale cartoon. He also sometimes made auxiliary cartoons of prominent heads–like those illustrated on the title page. Raphael’s design preparations seem more elaborate and rational than those of his contemporaries. In general, he seems to refine and perfect his inspiration in a more organized fashion than they. But eventually, his method of drawing preparation became canonical in European art.

When Pope Julius II invited Raphael to Rome in 1508 to decorate the Stanza della Segnatura in the papal apartments, he must have produced hundreds of drawings in the process of designing the murals. (In all, three to four hundred drawings by Raphael survive–only about a tenth of his output.)

More drawings survive for the Disputà than for the other three walls combined. With the surviving Disputà drawings, one could trace nearly the entire process of creating the design, although the primi pensieri are missing. At an early stage, Raphael made preliminary modelli that were shown to the patron for his approval. The pope seems to have criticized the original invention, and Raphael came up with a new, more dramatic compositional design that won acceptance.

Raphael’s reworking of the left half of the lower register of the scene survives in a spontaneous pen drawing, Study for the Disputà (figure 3-19). Raphael initially attacked the sheet with a dry or “blind” stylus, leaving furrows in the paper that are invisible in a normal photograph. With ease and sweeping freedom, his stylus left incisions that marked the placement of the figures across the surface. On top of these lines, he easily builds forms with an exceedingly fluid pen line that conveys his excitement in creating relationships among the figures that lead the eye from the left foreground to the Eucharist on the right. Darker contour lines help distinguish foreground from background, and a very transparent wash reinforces broadly spaced diagonal hatching. Both techniques define solid forms and establish a rhythm of light and dark. (Earlier, Filippino Lippi (figure 2-20) had also used wash to clarify and unify a design.)

3-19 Raphael, Study for the Disputà, 1509. Pen and ink with wash over stylus underdrawing, 24.7 x 40.1 cm. British Museum, London.

Although he must have made compositional studies for The School of Athens, all that survives are some drawings of groups and single figures—most of them solidly defined in silverpoint and white heightening on colored grounds—as well as an eight-meter-long, charcoal and chalk cartoon, now in the Ambrosiana Library, Milan. Although pricked for copying, it shows no signs that it was ever transferred to the wall.

3-20 Raphael, Four Fighting Men, 1510-11. Red chalk over stylus underdrawing, 37.9 x 28.1 cm. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. [flipped]

After the death of Julius II in 1513, Raphael continued to work for the popes in Rome. He set up an enlarged studio to handle the ever‑increasing number of commissions for tapestries, frescoes, and oil paintings. Although he always had control of a project, he seems to have sometimes worked side by side with other artists. Studio assistants, like Giovanni Francesco Penni and Giulio Romano, were trained to take Raphael’s ideas and turn them into modelli for the finished project. Their skill in imitating his style makes it difficult to determine the authenticity of many drawings connected with Raphael’s last works. Because of their assurance, strength, and finesse—rather than their style—connoisseurs have assigned to Raphael a choice number of drawings from this period.

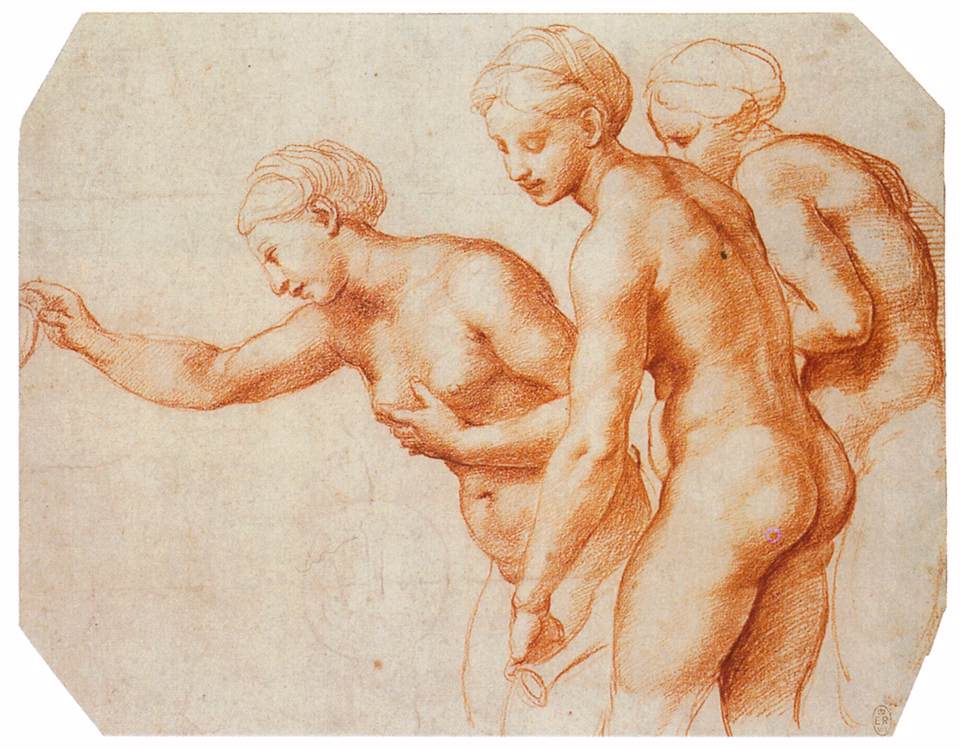

3-21 Raphael, The Three Graces, 1518-1519. Red chalk over stylus underdrawing, 20.3 x 26.0 cm. Royal Library, Windsor.

The Three Graces (figure 3-21), a red chalk study for figures that appear in a corner of a fresco on the ceiling of the Loggia of Psyche, has universally been accepted as Raphael’s. While his subordinates designed the majority of the composition, Raphael carefully rendered this group, which plays a minor role in the fresco. The drawing demonstrates an ideal of female beauty in opposition to Michelangelo’s muscular masculinity.

The drawing seems to combine three poses of the same female model as though she were in three stages of the same action. Red chalk dominated the period 1514-1518, and with it, Raphael developed a solid, dense sculptural style. Compared to the twisting lines of the fighting men, the Graces have the weight of sculpture. He achieved the effect by thoroughly modeling the entire surface of their bodies. He realized lights and darks with a network of fine hatched lines, which in places were rubbed to create even softer transitions. Nowhere does he use a generalized veil of dark to cover an area. The luminosity of the highlights suggests to the viewer the texture of polished marble and also, possibly, of soft skin. Did Raphael, unlike other artists at the time, actually use female models?

FLORENCE IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

The High Renaissance style in Italy, first manifest in Leonardo’s Last Supper in Milan and Michelangelo’s Pietà in Rome, flourished in Florence in the opening years of the sixteenth century. Except for Michelangelo’s David and Raphael’s Madonnas, the major Florentine accomplishments in those years were in drawing, most notably Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s cartoons. Their drawings were the legacy handed on to the next generation of Florentines when Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo left Florence in 1508. The best of the artist remaining in Florence were Fra Bartolommeo, who was actually a few years older than Michelangelo, Andrea del Sarto, and Pontormo. Each of them profited from the drawings of their three forerunners.

Fra Bartolommeo (1472/75-1517) The Florentine painter Baccio della Porta assumed the name Bartolommeo when he entered the Domincan convent in Prato in July 1500. He pioneered the use of black chalk as a sketching tool in Florence, as did Luca Signorelli in provincial Tuscany. Most of the 1100 sheets by Fra Bartolommeo still in existence are studies of individual figures in black chalk—relatively finished drawings that the artist and his collectors cared to preserve. Only in his last years, starting in 1511, did he sometimes use red chalk for faces and nude parts of figures. In his early years, he usually reserved pen and ink for compositional drawings.

Pen in hand, Fra Bartolommeo at first practiced a workmanlike manner of drawing, clouded often with murky areas of hatching. Black chalk in hand, Fra Bartolommeo exploited the breadth and depth of the medium to create massive saints and holy persons.

The early Study for Christ (figure 3-22), made in the final stages of preparation for a fresco of The Last Judgement, is a typical example of such figures.

3-22 Fra Bartolommeo, Study for Christ, 1499. Black chalk heightened with white on gray prepared paper, 28.4 x 20.9 cm. Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

He smoothly blended the black chalk with a great amount of white so that the cloak of Christ stands out from the gray of the paper in a very three-dimensional way. Study for Christ and many of his figure studies seem to be in reality drapery studies. They resemble the brush-on-linen drapery studies that Leonardo made while still in Verrocchio’s studio (figure 3-1). Obviously, other workshops in Florence continued to drape cloth soaked in wet plaster across a mannequin for drawing practice long after Leonardo left town in 1483. Derived from a mannequin, the anatomy of the figure under the bulky drapery seems a little disjointed and wooden. It is likely that the artist never drew a preliminary nude study for the Christ figure. Vasari recounts that a year or so earlier, in 1497 or 1498, Baccio burned all his drawings of nudes in a bonfire of the vanities set by the followers of Savonarola.

As a monk, Fra Bartolommeo gave up painting for four years. When he resumed drawing in 1504, Michelangelo, Leonardo, and Raphael were at work in Florence. Despite their presence, it was a trip to Venice in 1508, where he admired Giovanni Bellini’s late altarpieces, and a trip to Rome in late 1513 or early 1514, where he saw the Sistine ceiling and the Stanza d’Eliodoro, that recharged his drawing. A friend of Raphael and probably of Michelangelo, Fra Bartolommeo might have been able to study their drawings in Rome too.

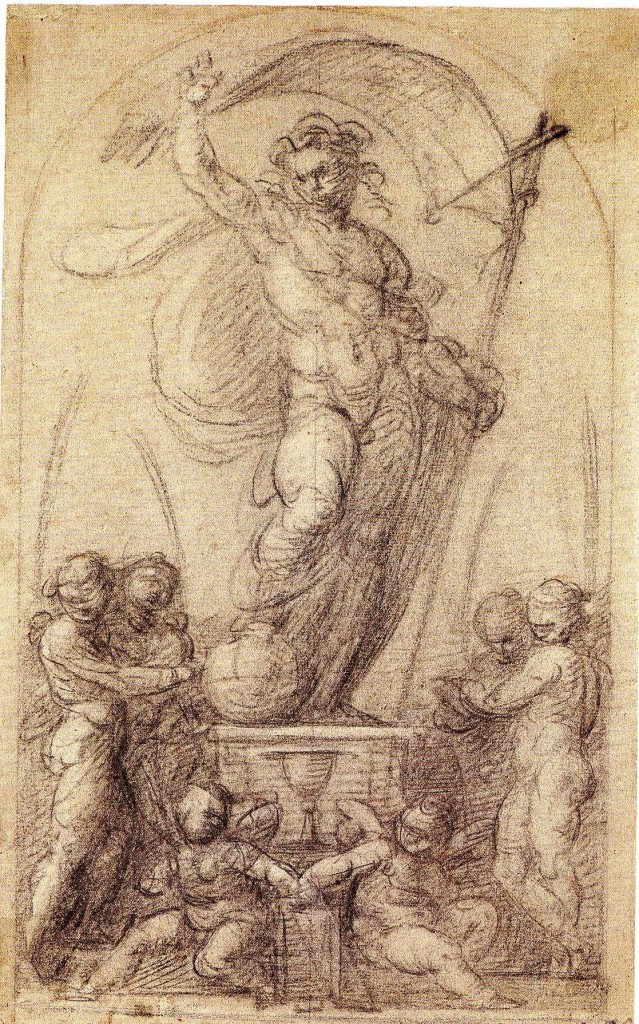

3-23 Fra Bartolommmeo, Study for the Pitti ‘Salvator Mundi’, 1516. Black chalk heightened with white on paper colored brown, 26.8 x 16.7 cm. British Museum, London.

Study for the Pitti ‘Salvator Mundi’ (figure 3-23) differs from his earlier Study for Christ in every way—except that it is still in black chalk. Now at the end of his career, he easily tossed off a dozen such studies for the composition of the painting, almost all of them in chalk rather than in pen. Instead of focusing on modeling, the later drawing displays energetic lines and massive figures that create three-dimensional space around the pedestal. On the pedestal, a nude, as muscular as any by Michelangelo, throws his left shoulder back and projects his right arm and leg toward the viewer. The emphatic curves of the bulging muscles radiate outward in the lines of the billowing cloak and pennant. Parallel hatching was applied with equal vigor. Little of it seems to have been rubbed and blended as in the earlier drawing.

Before and after he joined the Dominican order, Fra Bartolommeo liked to make delightful landscapes, drawn in pen, of the towns, farms, and convents he observed in the Tuscan countryside. Some of the places can still be identified, and some sketches are so spontaneous and fresh, they appear to have been rendered at the site. A Wooded Ravine (figure 3-24) is breathtaking in the simplicity of means that signals so much information. The lightest touch of the pen suggests trees, rocks, and water in strong outdoor light. The composition is ordered, but not along the diagonal lines of Titian’s landscapes. Fra Bartolommeo created a parallel design by penetrating space both down the stream and up the road. Like A Wooded Ravine, the over fifty landscapes of his that survive are remarkably early pure landscapes, not the setting for a biblical story or a mythological allegory.

Andrea del Sarto (1486-1530) The most active painter in Florence during the teens and twenties of the sixteenth century was Andrea del Sarto. As an apprentice, he had avidly studied the battle cartoons that Michelangelo and Leonardo left behind. He imitated some of the nude figures in Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina in which short chisel-like hatching strokes crisscross the surface of backs and arms to mold a relief of hills and valleys. But for the most part, Sarto continued the Florentine tradition of diagonal hatching and solid contours. The great majority of his drawings are in red chalk although he used some black chalk in his early years. On the rare occasions that he picked up a pen, he handled it as he did a piece of chalk.

Like other Florentines of his generation, he made disegno the central factor in his art. Consequently, he expended his creative energies in drawings—over a hundred of them for each project, inventing and refining the design in new drawings at every stage. Enough of them still exist to enable us to follow the process, although modelli and cartoons by his hand are quite rare. He evidently made cartoons for frescoes but probably not for oil paintings. Almost all his drawings are studies of the model or of details of the model or of drapery. They were made to clarify a problem. He had an unsurpassed talent to note what he saw quickly and accurately, and he seldom took the time to polish or elaborate his sketches.

3-25 Andrea del Sarto, Sketches for ‘Madonna del Sacco’, 1525. Red chalk, 29 x 26.1 cm. British Museum, London.

Sketches for ‘Madonna del Sacco’ (figure 3-25) illustrates Andrea’s first ideas for his highly praised fresco painting know by that nickname. To catch the image in his imagination as he attempts new solutions, he barely takes time to block in the figures. In three of the sketches he adds diagonal hatching for emphasis rather than modeling. Pentimenti are common, but rather than readjust the idea too much, he tossed off a new idea—Mary on one knee, Mary on both knees, the Child on her lap, the Child climbing off it. In two of them she has to bend over awkwardly because of the confined semicircular space.

The sheet of sketches does not include the definitive idea for the fresco: a counterbalancing figure of St. Joseph reclining on a sack. Once the decision was made to include the bearded St. Joseph, Sarto posed a youthful nude model on a sack in order to study the foreshortening and to study the fall of the light from the left, which puts St. Joseph’s face in shadow (figure 3-26). To increase their monumentality, without cramping them in, he realized that the figures in the lunette would be seen from below. To accommodate the low point of view, he lowered the left shoulder of the model.

3-26 Andrea del Sarto, Study for St. Joseph in the Madonna del Sacco, 1525. Red chalk, 14.6 x 15.6 cm. Louvre Museum, Paris.

Even though Michelangelo returned to Florence six years earlier (in 1519), Sarto is not concerned with an idealized, statuesque, and muscular interpretation of the model. Instead, broadly spaced, generally diagonal hatching mainly indicates areas of shadow. Sarto’s greatest achievement as a draftsman was in capturing the essence of the model in spontaneous sketches.

Pontormo (1494-1557) The artist Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci) was a much more inventive draftsman, who expanded the meaning of disegno. Before Leonardo left Florence in 1508, the fourteen-year-old Pontormo spent a few months with the much older master. The time was too short for the apprentice to absorb fully Leonardo’s style, but he seems to have grasped the idea that drawing could be used for experiment and discovery. A few years later (1512-14), he joined Andrea del Sarto’s shop, but the strongest lessons were learned from Fra Bartolommeo’s vigorous new manner after his trip to Venice.

3-27 Pontormo, Study for Vertumnus and Pomona, 1519-1521. Red chalk over faint black chalk, 40.5 x 26.2 cm. Uffizi, Florence.

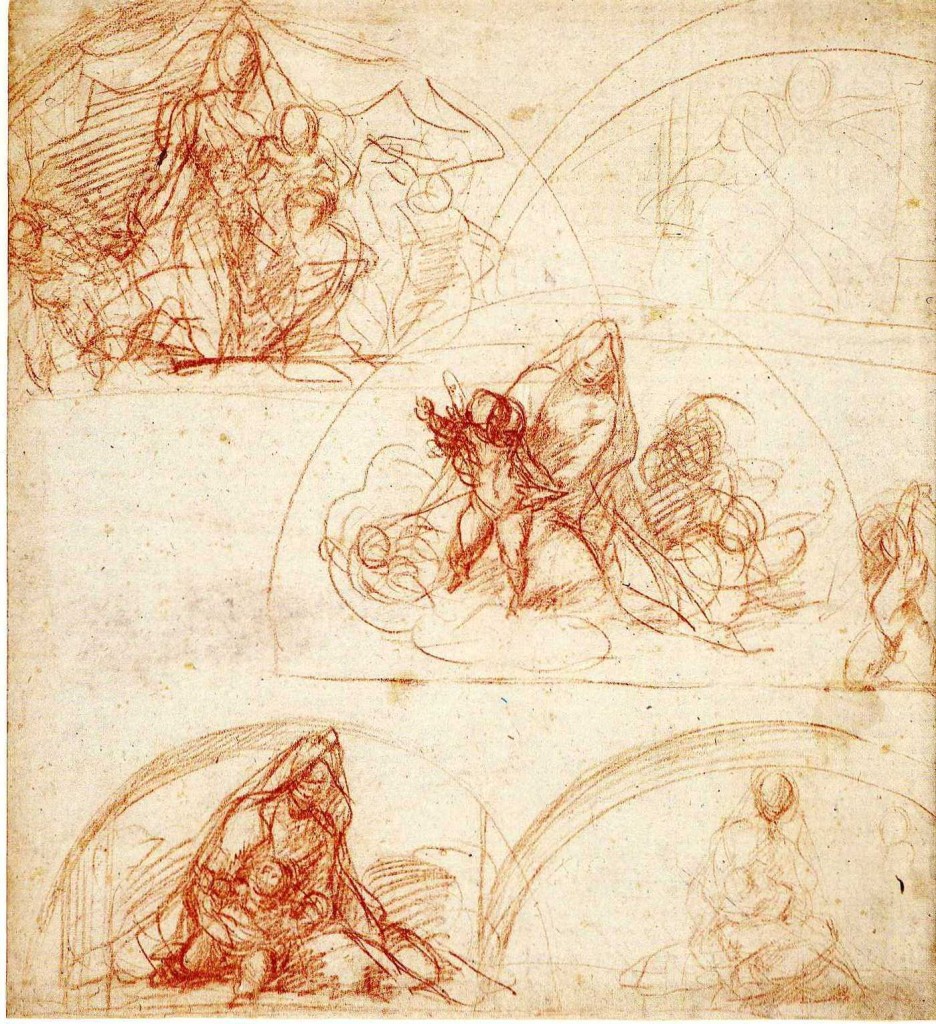

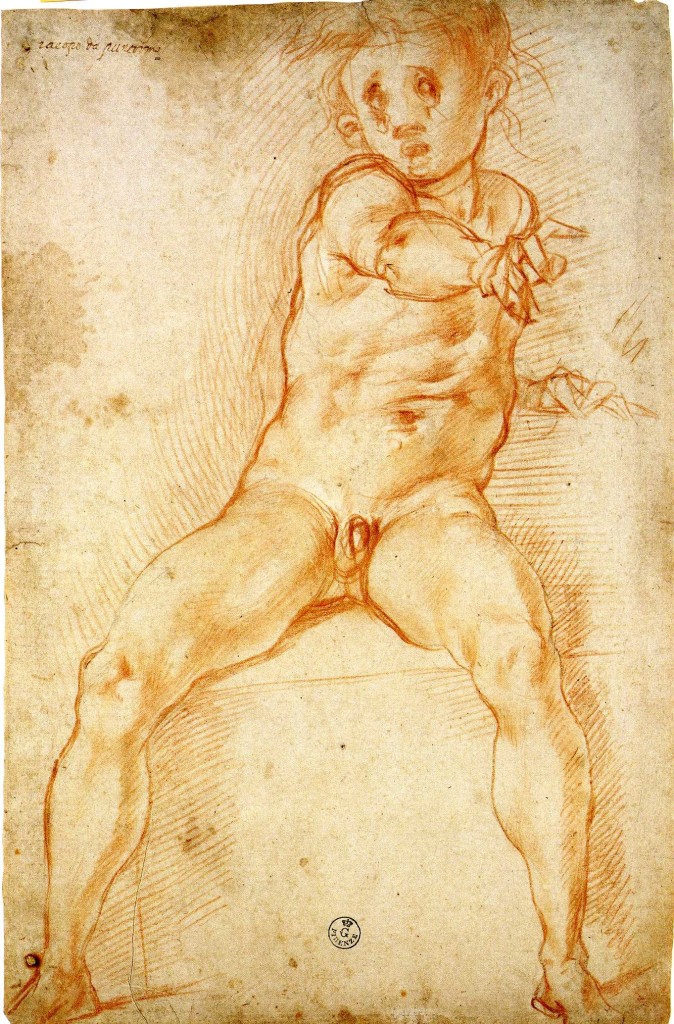

Of the nearly 400 drawings by Pontormo that remain, almost all of them are in red or black chalk. Most of his drawings, including Study for Vertumnus and Pomona (figure 3-27), can be connected with documented oil or fresco projects—in this instance, the lunette in the Medici villa at Poggio a Caiano (1520-21). The drawing resembles one of the five nude boys in the fresco, but it is not strictly speaking a study for any one of them. It was Pontormo’s habit to develop free sketches tangential to the task at hand—extra drawings made for their own sake. Pontormo may well have employed a model, but the drawing is essentially a variation on the pose of Haman and the ignudi from Michelangelo’s ceiling in the Sistine Chapel, which Pontormo had probably just visited.

Study for Vertumnus and Pomona is a virtuoso’s display of foreshortening and elegance of line. Guided by a preliminary faint black chalk sketch, the red chalk contours gracefully flow around the figure, even as pentimenti in the shoulder area shift the torso further to our right and twist the abdominal muscles. Traces of a blocky and angular style of drawing, which Pontormo sometimes used in his roughest sketches, appear in the hand and lower thigh of the adolescent. Inside the contours, judicious hatching models the anatomy. Outside the contours, more vigorous hatching seems to radiate from the figure. As in many of his figures from this period, Pontormo drew the mouth open and rendered the dark, deep-set eyes as vertical ovals. Whatever his conscious intentions, the conventions convey intense anxiety.

Mannerism in art has been defined in a number of ways, and this drawing fills most of the definitions that try to explain the style in terms of anti-classsicism or anti-naturalism, sophistication or virtuosity. The study is anti-classical in the sense that it goes beyond the norms of High Renaissance drawing still practiced by Andrea del Sarto. The thrusting arm and spread legs are an abnormal pose, not found in the classical tradition. It is primarily a sophisticated variation on another artist’s (Michelangelo’s) art, rather than based on nature. It is a showpiece of virtuosity, rather than a utilitarian part of the painting process. Some writers contend that the nude’s free-floating anxiety is also characteristic of Mannerism. In sum, the drawing does not manifest High Renaissance classical grace and harmony, but expresses the eccentric character of the artist.

While working on frescoes of the Passion in the Certosa di Val d’Ema a few years later, Pontormo discovered the graphic work of Dürer, especially his Small Passion woodcuts. In the few drawings that survive from the project, figures became thinner, elongated, more abstract, and more spiritual. The little modeling he used on them enforces an impression of weightlessness. He even imitated the broken and angular drapery folds of the German artist. By 1530 Pontormo’s Mannerism was in full bloom. Fra Bartolommeo and Sarto were both dead, and Michelangelo, his artistic obsession, had returned to Florence. Pontormo was the leading painter of the aristocratic Medici city.

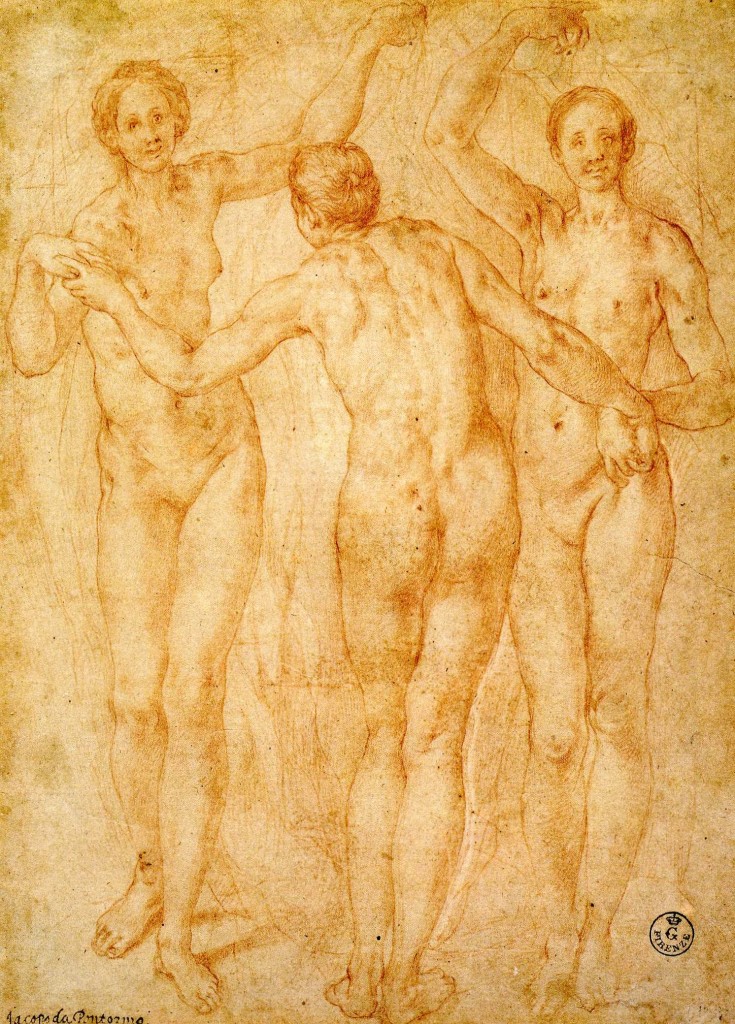

3-28 Pontormo, The Three Graces, ca. 1535-36. Red chalk, outlines incised for transfer, 29.5 x 21.2 cm. Uffizi, Florence.

Like Michelangelo in the mid 1530s, Pontormo did chalk portraits, including several revealing self-portraits, and made what seems to be presentation drawings, such as The Three Graces (figure 3-28). Like many study drawings of the period, The Three Graces is finely finished, literally from head to toe.

Most noticeably, Pontormo deliberately elongated the Graces. The length of head in relation to the length of the entire body is in a ratio of approximately one to nine. Also, he posed them with their feet together so that they appear to taper even more. The middle Grace, bending forward, tucks under the arm of her companion. The absence of overlapping and the gentle modeling contribute to the lack of three-dimensional space. The rhyming curves of their bodies and parallel diagonals of their arms create patterns across the surface that are stronger than any sense of substance or depth. These Graces are appropriately ethereal. They spring, not from observing the norms of nature or the art of Michelangelo, but from a disegno interno, an internal image Pontormo strove to make manifest in his art.

The prolific and popular artist Federico Zuccaro coined the phrase “disegno interno” when he lectured about the meaning of disegno before the Academia del Disegno in Rome in the 1590s. He found the roots of disegno in the words Dio and segnare, combined as di-segn‑o. Disegno, in short, was the sign of God within the artist—a spiritual inspiration not governed by the earthly rules of mathematics or geometry. In the artist’s mind, it is an image of pure form without substance, which flows directly into the lines of a drawing. Michelangelo, Vasari, and Pontormo expressed similar ideas earlier in the century. However, by the time Zuccaro published his theories in L’idea de’ pittori, scultori, et architetti in 1607, a new aesthetic and new meaning of disegno had appeared.

Pontormo devoted the last ten years of his life (1546-56) to painting frescoes of mostly Old Testament subjects, such as The Deluge, in the clerestory and lower walls of the choir of the Medici church of San Lorenzo in Florence. They were destroyed in 1742. Verbal descriptions and about 30 drawings are all that remain of his last great project. Like Michelangelo and Leonardo in their final years, Pontormo used black chalk. Several of the drawings are single figure studies; most of them are, atypically, compositional studies of groups of figures, such as Study for the Deluge (figure 3-29). The early single figure studies for The Deluge did not evolve far from the elegant and sophisticated lines of The Three Graces.

3-29 Pontormo, Study for ‘The Deluge’, San Lorenzo, 1550-1555. Black chalk, 26.6 x 40.2 cm. Uffizi, Florence.

However, the late studies of groups of figures are bundles of interwoven serpentine figures that betray Pontormo’s renewed involvement with Michelangelo and probably a visit to Rome to see his Last Judgment.

Study for the Deluge looks like a Rubik’s Cube of convoluted, intertwined nude bodies, most of them seen from the back and many of them faceless. Pontormo encased blurred modeling within a few wiry contours. He made it almost impossible to pull them apart visually. The contour lines of the swollen bodies create some circular, interwoven movements, but no discernable pattern overall. Lacking Renaissance grace and beauty, the pile of bodies also abandons Mannerist habits of sophistication and elegance. Pontormo’s inaccessibility makes it impossible to know what meaning he gave to the Flood’s destruction of mankind. We can only shudder that Pontormo’s nightmare looks forward to the photographs of American atrocities at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.