IMPRESSIONIST DRAWING

Daumier made very few drawings in preparation for his paintings. Instead, he painted directly on the canvas with only a preliminary sketch underneath. In the second half of the nineteenth century, fewer and fewer artists thought of drawing as a preparation for painting. As a consequence, drawing broke free from its subordination to painting.

Nevertheless, most artists of the next generation, including the Impressionists, continued to make drawings. Pissarro and Degas were life-long prolific draftsmen who valued drawing and, swimming against the current, made drawing central to their art. Manet, Monet, Morisot, and Renoir made abundant drawings, at least at certain periods. Drawings were a major part of the eight Impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1886.

Just as Delacroix in the Romanic period realized that a drawing best captured his inspiration, so too many artists in the Realist and Impressionist periods believed that a rapid drawing best captured their immediate contact with nature. The drawings and lithographs of Daumier set an example of speed, of grabbing the immediacy of experience. In order to take hold of the fleeting sensations of natural light and moving form, these artists likewise adopted spontaneous, rapid-fire methods of drawing. Extensive labor to finish and polish a drawing removed it from face-to-face, moment-by-moment perception. Since their range of sensations included color, Realist and Impressionist artists embraced media like pastel chalks.

![6-21 Eugène Boudin, On the Beach, 1863. Pastel [and watercolor?], 18 x 30 cm. Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet.](/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Boudin0623.jpg)

6-21 Eugène Boudin, On the Beach, 1863. Pastel [and watercolor?], 18 x 30 cm. Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet.

The drawing is a complete composition, but its sketchiness tells us that the artist rushed to capture a particular moment of time before it changed. He smudged the white pastel into the blue of the sky to represent vaporous clouds in a moist atmosphere. He made heavy dabs of pastel to indicate the human figures who shimmer like a mirage on the warm sand. The high-keyed and luminous baby-blue sky complements the bright blond sand. Several strokes of bright orange complement a few strokes of intense blue in the woman’s dress. Boudin obviously made On the Beach outdoors, stationed in front of the scene he witnessed. Boudin’s truth to nature and his alla prima pastel technique foreshadowed the methods of Impressionism. In fact, he exhibited six pastels at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. Four of them were called “sky studies.”

Baudelaire, in his review of the Salon of 1859, wrote that he had recently visited Boudin’s studio where he saw “several hundred pastel-studies, improvised in front of the sea and sky. . . . On the margin of each of these studies, so rapidly and faithfully sketched from the waves and the clouds (which are of all things the most inconstant and difficult to grasp, both in form and in color), he has inscribed the date, the time and the wind: thus for example, 8th October, midday, North-West wind.” They were all cloud studies without the human figure—a fact Baudelaire deplored, despite his enthusiasm for the drawings. Baudelaire’s visit confirms that Boudin was a pioneer in capturing specific effects of daylight while working in the open air.

As the hundreds of cloud studies also indicate, Boudin was a prolific draftsman. The Louvre has 6000 of his drawings in its collection. In addition to his beach scenes from the 1850s and 1860s–his most popular subject with collectors–he also drew large numbers of boats and fishermen and many, many cows.

Claude Monet (1840-1926) Claude Monet always led the public to believe that he painted his canvases outdoors in the presence of his subjects, without resorting to preliminary sketches. His assertions fostered the notion that he did not draw and had no use for drawing. On the contrary, he produced a substantial body of graphic work—work that played a major role in his art.

As a teen in the 1850s, he specialized in drawing caricatures. In the early 1860s, under the guidance and example of Boudin and Johan Barthold Jongkind, he brought to a finish several dozen black chalk landscape compositions. More importantly, in those same years he started to make the two other kinds of drawings that more directly affected his painting: pencil drawings in small sketchbooks or notebooks and pastel compositions on separate sheets.

6-22 Claude Monet, The Porte d’Aval Seen from the Cliff Path, Sketchbook 4, fol. 28v., ca. 1885. Pencil, 11 x 19.5 cm. Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet.

Until illness confined him to his garden in Giverny, Monet habitually walked the northern countryside and coastline of France scouting for motifs he might paint. Now and again he took note of a scene with a bare outline drawing in a pocket-size sketchbook (figure 6-18). Later on, the drawings helped him decide whether to return to the scene with his paints, canvas, and easel. In the sketchbook drawing, The Porte d’Aval Seen from the Cliff Path (figure 6-22), he retraced and reasserted with darker lines the serpentine contours of the cliffs as he reconsidered the virtues of this particular motif as a composition. Vertical framing lines on the left and right adjust the proportions of the design.

Many other drawings in the sketchbooks contain even fewer and fainter lines than those in this example. Sometimes, merely three lines register the smooth contours of two hills and the horizon. Most of the 400 sketchbook drawings have no chiaroscuro to indicate light, no annotations about color, and very little perspective illusion. In all his sketchbook drawings, Monet rejected the tradition of landscapes staged in the manner of the Poussin and Claude Lorraine. He sought to establish only a linear armature on which he could paint his sensations of color, whether they were near or far. In other words, it was in his sketchbooks that he worked out his ideas about composition, including designs for his series of paintings of haystacks, the Cathedral of Rouen, and waterlilies.

The Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris now owns the eight sketchbooks Monet left in his studio at his death. Two other sketchbooks have been lost and another disassembled, its contents dispersed.

6-23 Claude Monet, Broad Landscape, ca. 1864-66. Pastel, 17.4 x 35.9 cm. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts.

Monet sometimes carried a set of pastels and larger sheets of paper with him on his excursions. These dry colors allowed him to instantly capture an effect of light that lasted only moments. The pink light on the clouds in Broad Landscape (figure 6-23) presumably disappeared within minutes. Like many of his pastel landscapes from the 1860s, Broad Landscape is basically an examination of the light and color of clouds. He possibly drew several of them in rapid sequence as the illumination changed over time. The immediacy of pastel enabled him to fulfill his aspiration to be absolutely true to nature.

The pastel cloud studies from this period tend to be panoramic compositions with only a few essential lines like many of the simple designs in his sketchbooks. In this sample, the two wedges of hills intersect at the vertical object in the center. He applied the pastels in broad, rugged strokes on a warm beige paper visible through the colors that he sometimes overlaps and sometimes blends. Pastel let him explore color relationships: the green hill complements the red in the sky and the yellow ochre hill accentuates the blue of the water, horizon, and sky.

He modeled his technique on Boudin’s. In fact, in 1858, the year before Baudelaire saw Boudin’s pastels of sea and sky, Boudin invited the eighteen year old Monet “to draw with him in the open field.” Monet’s pastel (figure 6-23) also lacks the human anecdote that Baudelaire missed seeing in Boudin’s drawings. Although Broad Landscape was a rapidly made sketch, Monet completed every corner of it, signed it, and sold it to his dealer Durand-Ruel in 1891.

At the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, Monet exhibited seven untitled pastels alongside five oil paintings. He considered most of his one-hundred-plus pastels independent works of art. They are almost never preliminary studies for oil paintings. As an indication that they were complete in themselves, he signed three-fourths of them. Monet worked in pastel in three periods: from the early1860s—when he worked alongside Boudin—up to the exhibition of 1874; in the early 1880s; and finally in London in 1901 when his canvases and oils were slow to arrive from France. Except for these twenty-six Thames landscapes, all his pastels depict a small area in Normandy where he grew up and where he kept company with Boudin.

Edgar Degas (1834‑1917) Edgar Degas always recalled with great pride that as a young artist, he had met Ingres. At that meeting, the Master told Degas, “Draw lines (“Faites des traits” [literally, “make strokes”], young man, many lines, whether from memory or from nature.” This jejune advice inspired Degas for half a century. When he met Ingres in 1855, Degas had already been drawing with Louis Lamothe, a pupil of Ingres and Hippolyte Flandrin. But instead of completing a full course of study at the Academy, Degas pursued his academic training by spending most of the 1850s, when he was in his twenties, copying paintings in the Louvre and prints and drawings in the Bibliothèque Nationale. He copied classical sculpture; the works of Raphael, Leonardo, and Marcantonio Raimondi; and much more. (Someone has counted 740 existing copies.) On a visit to Italy, from 1856 to 1859, he even drew a student’s obligatory series of académies in the studios of the French Academy in Rome. During his formative years, he probably never saw more than a drawing or two by Ingres (except stained glass window designs) until 1861 at an exhibition in Paris at the Salon des Arts-Unis.

Degas made a great many of his copies in notebooks or sketchbooks, most of them small enough to fit in his pockets. Indeed, over a thirty-four year period, from 1853 to 1886, he filled at least thirty-eight notebooks with 2000 pages of drawings and 500 pages of written notes and quotations. At his death, the notebooks, intact and in good condition, sat in his studio. Most of them are now in the Bibliothèque Nationale. Unlike many of his drawings on loose sheets, the notebooks can be dated, and they thus provide a chronicle of his activity as an artist and of his development as a draftsman.

6-24 Edgar Degas, Copy after the head of the infant Christ from Leonardo da Vinci’s “Virgin of the Rocks,” Notebook 1, p. 36B, ca. 1853. Pencil, ca. 1.3 x 3.5 cm. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale.

In the early notebooks, Degas recorded the art that he saw and the places that he visited in cautious and delicate pencil strokes, as in his impersonal copy of the head of Christ from Leonardo’s painting, Virgin of the Rocks (figure 6-24). Typically, he copied only a part, seldom the whole, of a composition. In this copy, he used long diagonally parallel hatching strokes to reproduce Leonardo’s pervasive sfumato—just as the Florentine artist had done in his drawings. (See figure 3-3.) But in 1859-1860, especially in notebook 18, Degas began imitating the storm and stress of Delacroix’s paintings with swift ink lines, washes and watercolor accents, or rapid diagonal hatching for more expressive chiaroscuro. Very likely, he never saw a Delacroix drawing in those years either.

After the mid-1860s, he no longer used his notebooks for copying other artist’s work but for rapidly seizing the essential lines of the horses and jockeys he observed at the racetrack, singers performing in concert halls, and ballerinas rehearsing at the opera. The sketches provided material, drawn from the real world, for paintings that he planned.

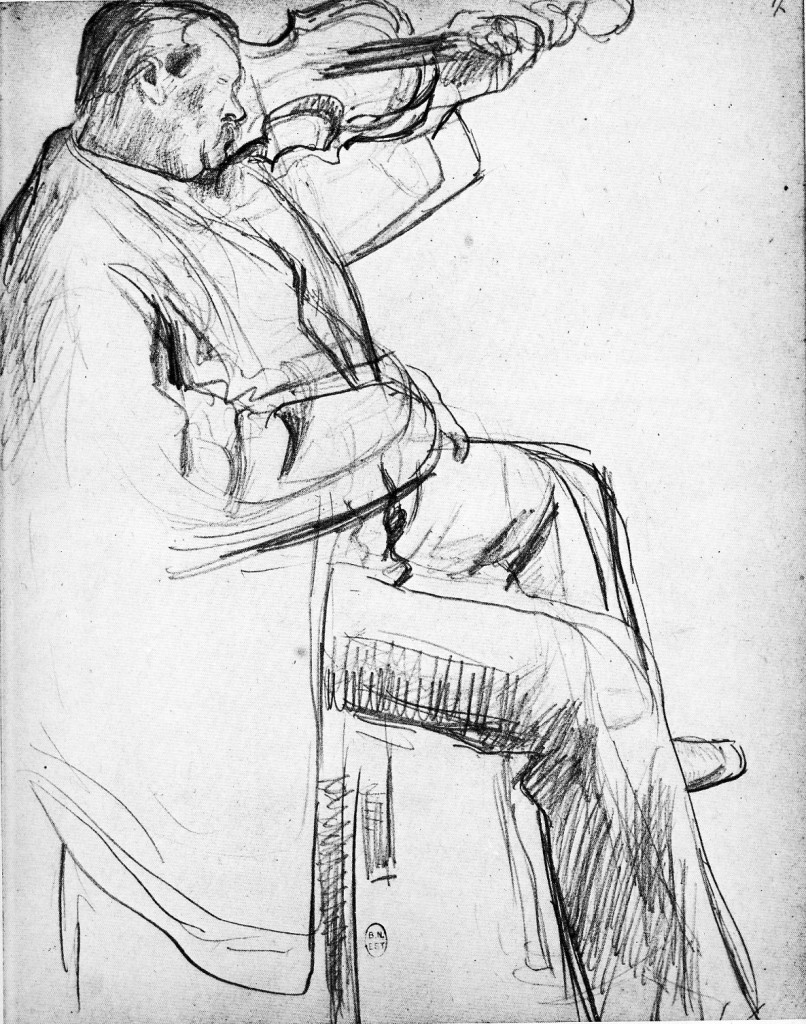

6-25 Edgar Degas, Study for École de Danse, Notebook 30, p. 17, ca. 1878-79. Pencil, 21.4 x 17.8 cm. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale.

The violinist he studied in figure 6-25 appeared in two paintings titled École de Dance (or The Rehearsal) from the late 1870s. The pencil lines are considerably darker and heavier than those in his early notebook drawings. Having gained self-confidence, he now drew forceful contours with spontaneity and a sure and steady hand. The visible pentimenti are not the result of uncertainty or an inaccurate eye, but adjustments to an arm or leg to position it higher or lower in relation to the whole. Along with some heavy hatching, he thickened some contours with repeated lines one on top the other—more in the manner of Millet than Ingres.

Apart from the notebooks, his earliest drawings were portraits of members of his family, for example, the portrait of his sister Thérèse de Gas (figure 6-26) when she was about fifteen years old.

![6-26 Edgar Degas, Thérèse De Gas, ca. 1855-56. Black crayon [Conté crayon] and graphite on brown/buff paper, 44.1 x 32 cm. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts.](/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/DegaSSC26113.fpxobjiip1.0wid400cvt.jpg)

6-26 Edgar Degas, Thérèse De Gas, ca. 1855-56. Black crayon [Conté crayon] and graphite on brown/buff paper, 44.1 x 32 cm. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts.

From 1859 to 1865, the years immediately after his “apprenticeship,” Degas painted six or seven narrative paintings drawn from the bible, history, or mythology. For each of these paintings, he made numerous sketches of nude and clothed figures, sometimes in his notebooks, more often on single sheets. The polished line and soft modeling of these drawings (e.g., Musée d’Orsay) also betray the academic style of Lamothe.

Even in later years, as an Impressionist, he would continue to base his art on drawing. In short, he followed the traditional method of artistic preparation codified by Raphael and reaffirmed by Ingres and his school in the nineteenth century. However, in the whole of Degas’s graphic oeuvre, compositional studies are few—by the early 1870s they disappear—and modelli are non-existent. He seems to have assembled his paintings like a mosaic from separate figure drawings.

In 1865, he abruptly switched from historical narratives to scenes of contemporary urban life, inspired perhaps by the example of Daumier and of Degas’s friend Manet. Degas first focused on horses and their jockeys at the racetrack. Although pencil was still his favorite medium in the 1860s, he experimented with bolder agents such as conté crayon, charcoal, and essence—paint with a very diminished oil content and so diluted in turpentine that it can be applied like quick drying ink wash.

6-27 Edgar Degas, Four Studies of a Jockey, 1866. Essence, ink, and gouache, 45 x 35.5 cm. Chicago, Art Institute.

Four Sketches of a Jockey (figure 6-27) was not drawn in preparation for a painting but as part of an informal encyclopedia of jockeys and horses that he worked on for decades. This sheet contains four entries, as it were, placed in a balanced arrangement on the page. He devoted the sheet to only unconventional rear-view poses of the faceless jockey. The two sketches on the left vary but slightly. On the right, he viewed the jockey at the top from the side, and in the bottom right the jockey turns and stabilizes himself with a hand on the horse’s rump. Degas’s sheet of four sketches brings to mind the sheets of Watteau (figure 5-3) in which he caught the same figures in a cascading variety of poses.

Degas first stained the paper a warm transparent brown with essence, which probably has turned darker than he originally intended. The essence established a middle value as a ground, just as the old master painters had applied a darkish ground to a canvas. From this base, Degas then drew the darker contours of the horse and rider. A mere two or three lines suffice to convey the bulk of the horse. Finally, with white gouache, he brushed on bright highlights that replicate the sheen of the jockey’s silks.

A few years later, in the 1870s, he often drew ballet dancers in essence on vividly colored blue, pink, green, or yellow paper over pencil or chalk sketches. He showed several of these at the Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876.

In Four Sketches of a Jockey, drawn a decade before he studied the violinist in his notebook (figure 6-25), Degas’s hand had already attained the skill to make spontaneous strokes that hit the mark every time. His confident ability sprang in part from the fact that he usually did not draw in essence directly from life but from earlier drawings. All the repetition in these drawings implies that Degas interpreted Ingres’s exhortation to draw a lot of lines to mean that an artist should draw the same thing again and again. Degas himself often urged other artists to “make a drawing, make it again, give it a rest, make it again and pause once more” (Hans Graber, Degas, 1942, p. 92). He had an obsession to extract every possible variation from a visual idea. Although no two figures that he drew were ever the same, after a while Degas could draw a pose or motif from memory.

![6-28 Edgar Degas, Little Girl Practicing at the Barre, ca. 1878-1880. Black chalk heightened with white [chalk?] on faded pink paper, 31 x 29.3 cm. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.](/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/DegasGirlDP805820.jpg)

6-28 Edgar Degas, Little Girl Practicing at the Barre, ca. 1878-1880. Black chalk heightened with white [chalk?] on faded pink paper, 31 x 29.3 cm. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

At the top of the drawing, Degas made a note to himself in chalk to “emphasize the elbow bone” if and when he might rework the drawing in his studio. At the bottom of the drawing, he wrote in pencil the name of the ballet movement for the sake of Louisine Elder, the future Mrs. Charles Havemeyer, who bought the drawing from Degas with the guidance of their mutual friend, the artist Mary Cassatt. Degas also signed his drawing in pencil at the time of sale. After his death, more than 1400 of the drawings that remained in his studio were cataloged and sold in four lots, stamped with the same signature in red-orange ink.

At the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition in 1886, Degas showed only two oil paintings and ten ambitious pastels. (More about his pastel drawings in a moment.) The catalog matter-of-factly described the ten as a “sequence of female nudes, bathing, washing, drying themselves, combing their hair and having it dressed.” His models for these drawings had to hold transitory poses in the middle of these simple activities.

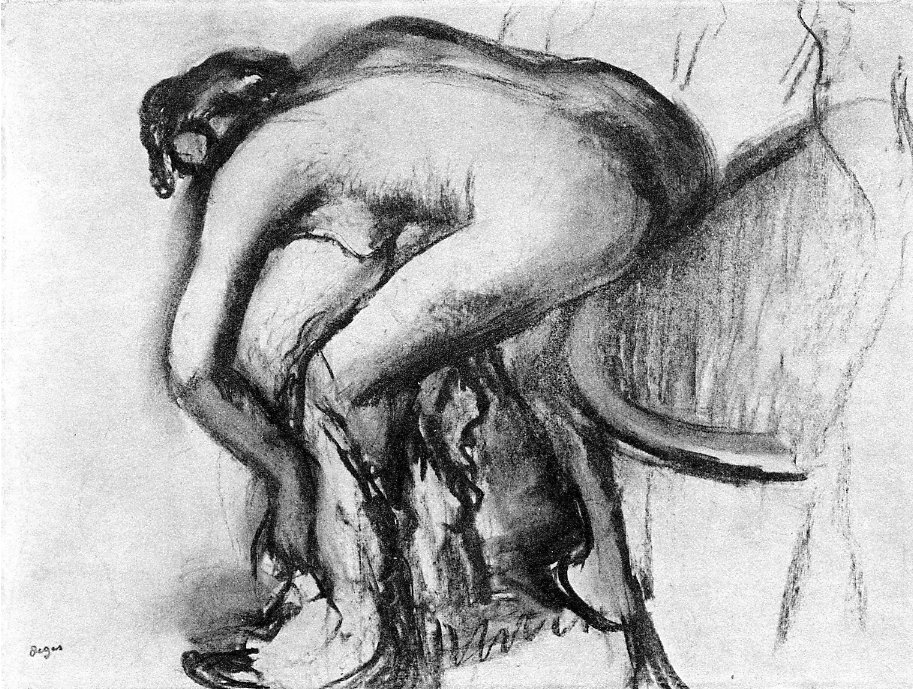

6-29 Edgar Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying her Legs, ca. 1900-05. Charcoal on tracing paper mounted on card, 40 x 54 cm. Stuttgart, Graphische Sammlung, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart.

From the 1880s on, the female nude became as important to him as horse racing and the ballet. In the early years of the twentieth century, when he drew After the Bath, Woman Drying her Legs (figure 6-29), he was still obsessing over women at their bath. The drawing is one of several versions of the pose of a nude bending over while perched on the edge of the tub. As he often did in his last years, he drew the woman by tracing an earlier drawing rather than by observing a posed model. Since smooth, translucent tracing paper discolored over time, Degas usually mounted the drawings on white bristol board to enhance the light and to support the thin paper.

In contrast to the slim, youthful proportions of his ballet dancers, his bathing women are mature, hefty types whose bulk strains against the confines of the sheet like the nudes that fill Greek metopes. The counter-curve of the tub and a few vague lines of a curtain on the right suffice for a setting. His line, made with a stub of charcoal, has become bolder as well as simpler. He reduced the thick contours of the nude to a few essential curves—a power-packed shorthand for the human body. He made areas of dark with crude and forceful hatching or stumping. He did not exploit the freedom and speed of charcoal but its bluntness, which translates, paradoxically, as grandeur. Without imitating any particular older style, Degas became a primitive before Picasso and Matisse ever did.

In the last few decades of Degas’s career, pastel became his preferred medium. The preference for pastel has been attributed to his declining eyesight, but the calculation and complexity of a late pastel such as Dancers (figure 6-32) demonstrates that he could see when and what he wanted to perfectly well. He preferred pastel because he could draw and color with it at the same time. Nineteenth-century manuals declared that pastel’s matte and opaque colors were more permanent than oil paint and were not darkened or dulled by varnish or a medium like oil. In pastel, Degas could apply color without elaborate preparation and without drying time and could thus stop and re-start a pastel drawing at any time without ill-consequence. Continually experimenting with their application, he was able to turn what was considered a delicate and fragile medium into a vehicle for complex and powerful expression.

Degas converted to pastel gradually—at first, for a few portraits of family members. Then, in 1869, he drew a series of landscapes of the Normandy coast in pastel. With their sweeping flat horizons and plentiful skies, they are clearly linked to the pastel cloud studies of Monet, Boudin, and Delacroix. But Degas drew his landscapes in his studio from his imagination, and they have the vagueness and moodiness of landscapes by his friend James McNeill Whistler. Degas also had an intimate knowledge of eighteenth-century pastel technique because his father collected works by La Tour, Perroneau, and Chardin. In the mid 1870s, reversals in the Degas family banking business compelled the artist to produce pastels, which he could make and sell more quickly than oil paintings. By the end of the decade, he was hooked on pastel. Eventually, he produced more pastels (over 700 of them) than paintings.

6-30 Edgar Degas, Dancer Adjusting her Shoe, 1885. Pastel on gray paper, 48.2 x 61 cm. Memphis, Dixon Gallery and Gardens.

Sometimes he merely added, so-to-speak, pastel color to charcoal or chalk drawings. In Dancer Adjusting her Shoe (figure 6-30), he colored the girl’s tights and bodice lilac and her ribbon blue and added yellow ochre hatching that radiates from her like a sunburst. Seen from a bizarre overhear viewpoint, her shape flares into a circle and her mundane activity generates as much energy and movement in the drawing as any dancer’s on the stage.

Degas took bolder steps with pastel when, in the late 1870s especially, he reworked over 80 monotypes with pastels. The monotype underneath Two Dancers Entering the Stage (figure 6-31), an early example of the procedure, is visible in the upper and lower left corners and in the torso of the foremost dancer.

6-31 Edgar Degas, Two Dancers Entering the Stage, ca. 1877-78. Pastel and pastel distemper over monotype in black ink on heavy white laid paper, 36.5 x 35.9 cm. Cambridge, Fogg Art Museum.

For most of these pastel drawings, Degas printed a second, much fainter impression from his monotype plate. For Two Dancers Entering the Stage, he first covered the entire plate with ink, then created a negative image by scraping and wiping the plate. In addition to providing a rough sketch for his composition, the monotype provided a murky dark ground on which to work. The pastel colors, springing from the dark areas of printer’s ink, match very nicely singers and dancers hit by bright stage lights in a darkened theater.

To color his monotypes, Degas sometimes experimented with moistened pastel sticks, a technique used by Rosalba Carriera. Or he might steam or spray a passage so that he could work it with a wet brush. He also pulverized pastel sticks and mixed the powder with water to create a paste, which he applied with a brush. He often combined dry pastel with applications of gouache or, in this case, distemper—pigment mixed with animal glue or casein (milk protein). The strokes of turquoise to the left of the dancers in figure 6-31 seem to have been manipulated with a brush.

Theater sets and ballet costumes always gave Degas the opportunity to willfully exploit color. By the end of the nineteenth century, when he drew Dancers (figure 6-32), the element of color seems to have become as important to him as that of line. He deliberately designed Dancers, a drawing as large as a small painting, around a harmony of the three secondary colors: orange, violet, and green. Furthermore, very much like the paintings of Monet, he broke surface areas into separate touches of contrasting color. The result is a shimmering surface texture of vibrant color.

Undoubtedly, a charcoal drawing lies buried beneath the layers of pastel in Dancers. With his pastel sticks, Degas methodically drew most parts of the figures with downward, parallel strokes. In contrast to the figures, the background is a jumble of squiggles and crosswise hatch marks. He modeled the figures and their costumes with color rather than with a shade of the original color. For example, areas of costume and flesh are shot through with strokes of green. (Degas surely knew that Perroneau had modeled with green.) Note also that the shadow cast by the torso of the foreground dancer onto her skirt is predominantly green, nearly the opposite color of the orange she wears. To impose one layer of pastel over another, without the second color tearing up or mixing with the first, Degas applied a fixative to the first layer. It was a secret formula, given to him by Luigi Chialiva. The fixative did not give the matte appearance of pastel a gloss or change the appearance of the color itself.

Degas has also flattened the three-dimensional space in Dancers, in other words, they have no room in which to stand. They appear to be on top of one another, poking each other with their elbows as it were. Only the element of color generates space: the foremost ballerina wears an orange bodice whose warm color next to cool blue and violet makes her come forward. Instead of an illusion of space, Degas created a balanced design across the surface. The two dancers on the right both adjust their shoulder strap with both hands. Degas probably copied them from an earlier drawing that established the pose. The left dancer, seen from the front, raises an arm as do her companions. Her upturned head balances that of the dancer on the right.

Who was the greater draftsman, Ingres or Degas? Ingres certainly had more pupils and followers than Degas and, consequently, had a greater impact on subsequent generations. But if variety, experimentation, innovation, and sheer ability, both innate or learned, are criteria that decide this contest, Degas wins hands down.

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) Apart from Degas, no French Impressionist drew as much as did Camille Pissarro. An inventory of his studio in 1903 lists approximately 2500 drawings. Pissarro biographer John Rewald estimated that there were over three thousand still in existence. The most representative selection of them—about 400 sheets—is in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Pissarro began drawing as a child on the Virgin Island of St. Thomas where he was born; he drew at Passy near Paris as a young teen while he attended school; and he drew when he returned to St. Thomas to work in the family business. His skills were noticed by the Danish painter Fritz Melbye, who went with Pissarro to Venzuela for two and a half years (November, 1852-August, 1855).

6-33 Camille Pissarro, Wooded Landscape on St. Thomas, 1854-55. Pencil, 34.5 x 27.7 cm. Oxford, Ashmolean Museum.

A surprising number of drawings still exists from his years in South America and the Caribbean, including Wooded Landscape on St.Thomas (figure 6-33), a drawing he made shortly before he left the island in late1855 for Paris. Like most other landscape drawings of his from this period, Pissarro constructed the scene almost exclusively with lighter and darker hatching. Value contrasts alone build forms and push and pull clumps of leaves in and out of space. Contour lines, where they exist, are broken and choppy. He obviously did not learn academic principles of drawing, which stressed a smooth all-encompassing contour. Instead, he most likely taught himself to draw from popular drawing manuals and book and magazine illustrations of picturesque places. Some of his early drawings are compositional studies of ordinary people and everyday places; others like Wooded Landscape on St. Thomas are studies made directly from nature, although he must have imagined the two figures at the base of the trees whose tiny size exaggerates the height of the trees.

6-34 Camille Pissarro, Study of a Tree (recto), ca. 1860-65. Pencil, 23.8 x 31.6 cm. Oxford, Ashmolean Museum.

In France, after a stab at academic drawing of the nude model, Pissarro gravitated quickly to the landscape style of Corot. Study of a Tree (figure 6-34) testifies that he was attracted to Corot’s style of drawing—not from the late 1850s or 1860s, but from decades earlier, the 1820s and 1830s. (See figure 6-11.) Pissarro saw drawings from those years in Corot’s collection and he eventually owned some of them. Unlike the previous tree study, in this drawing Pissarro precisely outlined the tree branches and their somewhat gnarled pattern of growth. His lines are refined and delicate in contrast to the earlier vigorous handling of the pencil. Like most of the drawings from this period, it is a more elaborated and less spontaneous composition, an independent finished drawing unrelated to any painting.

In fact, in the late fifties and early sixties Pissarro was imitating the technique and style of a number of landscape artists, and to that end he experimented with chalk, charcoal, wash, and colored paper. Like Corot and other Barbizon artists, he especially studied value contrasts. Notice that, because of a misty atmosphere, the woods surrounding the aged tree in figure 6-34 diminish in value and thus recede behind the prominent tree.

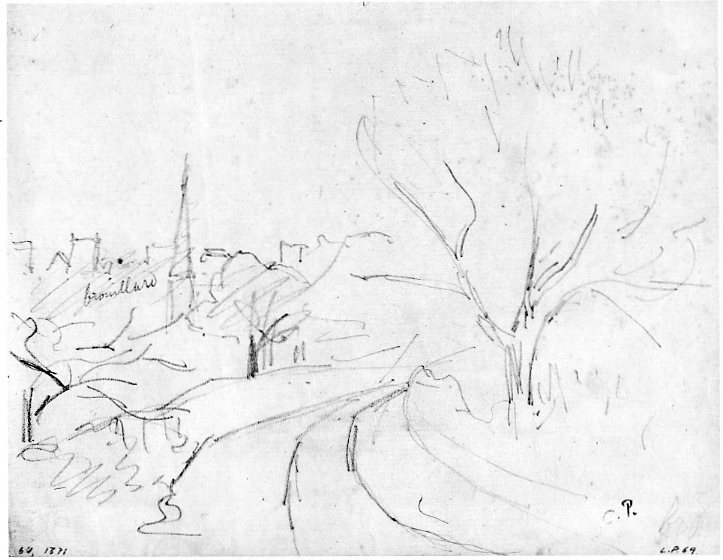

6-35 Camille Pissarro, Study of Lower Norwood, London, 1870-71. Pencil, 15.4 x 19.8. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum.

In the late1860s, Pissarro met Monet, Renoir, and Sisley at the Café Guerbois in Paris and in the small villages of Louveciennes and Pontoise, ten and twenty miles west of Paris, where he painted. In concert with them he became one of the founders of Impressionism. Like Corot and Monet, Pissarro began carrying small sketchbooks in which he made rapid, summary pencil drawings of motifs for possible paintings. As in Study of Lower Norwood, London (figure 6-35), one of several drawings he made of the motif, the relatively few lines and no hatching formed a matrix for hundreds of strokes of color when the design became a painting. (In England, where he sat out the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, he painted the church from another direction. He worked alongside Monet who was also in England for the war.) A few squiggles across the forms in the distance at the left and the word brouillard written over the squiggles reminded him that a mist enveloped those forms. Many other drawings from this period have color notations on them.

Nearly thirty sketchbooks by Pissarro have been identified; none of them remain intact. It is estimated that he made about half his drawings in them. After England, small sketchbook sheets with a landscape outline or with a sketch of only one or two figures are the rule for the rest of his life. Most often he carried with him a pencil or sometimes black chalk. He might rework a drawing in pen back in the studio.

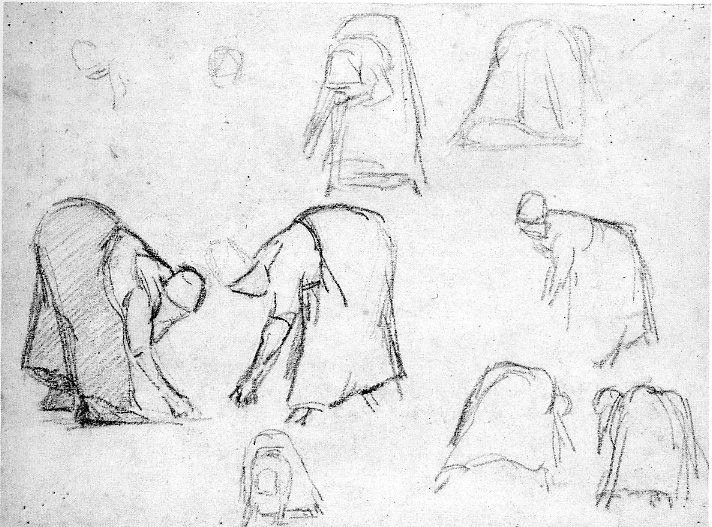

6-36 Camille Pissarro, Studies of Female Peasants Gleaning, (verso) 1874-1875. Black chalk, 23.8 x 31.6. Oxford, Ashmolean Museum.

Several years later, in 1874 or 1875, on the verso of Study of a Tree (figure 6-34), Pissarro drew Studies of Female Peasants Gleaning (figure 6-36) in a very different style. Numerous short strokes create rugged contours and give a blocky appearance to the figures, indicating the simple geometry underlying their shape. To accentuate the plane geometry, he kept all the figures parallel to the surface of the sheet or perpendicular to it. The only bit of hatching—on the figure on the left—does not round the shape but flattens it. In short, his drawing makes clear the essential structure of the forms.

At this time he was working side by side with Paul Cézanne, who shared Pissarro’s concerns for structural analysis. Both artists were influenced by the drawings of Jean-François Millet; Pissarro was also attracted to Millet’s peasant subject matter. As in Millet’s preparatory sketches (see figure 6-18), Pissarro used a multiplicity of short straight lines to build heavily reinforced contours. He could have seen the short lines that build a figure even in prints after Millet’s work. He also saw the drawings from Millet’s studio (and drawings from the Gavet collection) that were exhibited in Paris in 1875 before they were sold.

6-37 Camille Pissarro, Study of a Female Peasant Weeding, 1882. Black chalk with watercolor, 17.2 x 21.1 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre.

As Pissarro moved away from Monet’s form of Impressionist painting, he began to draw the human figure more and more frequently, more often than landscapes. In the 1880s, large-scale mostly female figures dominate his paintings and prints. As in figure 6-37, Study of a Female Peasant Weeding, most of the figures from that period bend and stoop while performing some rural task. The handling of the chalk shows that he has grown quite confident in his drawing. He roughs out the woman with strong broad lines, many of them repeated. The swirling lines on the ground on the left—whatever they may represent—are very aggressive, and the hatching elsewhere is equally bold. Unlike the flattened forms in figure 0-00, the figure moves toward us at an angle. As in other drawings of this period, he sparingly heightened the black chalk with watercolor.

It was no doubt Edgar Degas who, by word and example, encouraged Pissarro to draw more fluidly and experiment more courageously. The artists saw each other frequently during the 1880s. Although he did exhibit pastels at the fourth Impressionist Exhibition in 1879, Pissarro did not duplicate Degas’s technical experiments with pastel or other media, and he did not use pastel studies as the basis for oil paintings. Pastels constitute only about two percent of Pissarro’s drawings in any case. in the Caribbean and South America, Pissarro had worked out compositions for paintings in watercolor, and he took up the practice again in the late 1870s. (His very late watercolors rarely have any connection with oil paintings.) Like Degas, Pissarro employed his drawings as a repertoire of figure and landscape motifs for his paintings and prints, selecting and arranging them in his studio. Peasant Weeding was one of nine figure studies he made in a sketchbook for the painting Les Sarcleuses (Weeders), Pontoise, 1882, shown at the seventh Impressionist exhibition in 1887.

6-38 Camille Pissarro, Three Studies of a Woman Dressing, ca. 1895-1900. Pastel on pink paper, 46.1 x 60.8 cm. London, British Museum.

In the 1890s, often on larger sheets of paper, Pissarro continued to make figure studies which might later appear in one or another painting. For example, he reused the figures in Three Studies of a Woman Dressing (figure 6-38) in two gouaches and in an oil painting. He no doubt made Three Studies, like many other drawings, from a posed studio model. In the drawing, the three figures describe a cinematic sequence of a woman dressing: from left to right she buttons an undergarment, puts one arm in a blouse, then lowers a big striped skirt over her head. For added movement, the figures stand a step or two behind one another, as though the camera pulls away from the action. Over a tentative underdrawing in pencil or chalk, Pissarro applied with a sure hand only a few bold, broad strokes of pastel on the large sheet of pink paper. The fin-de-siècle yellow and pale blue enliven the drawing without any attempt to fill in the areas between the lines or outside them, as in Degas’s pastels. Modeling is nonexistent—the style is closer to Gauguin’s arbitrary colors and simple outlines.

For over fifty years, Pissarro changed his style of drawing in tune with the advanced trends of his day, from Barbizon Realism, to Impressionism, to Post-Impressionism. Through it all, his drawings are always concise and candid. In opposition to the myth that the Impressionists painted spontaneously and directly in front of nature, Pissarro like Degas found his inspiration and the substance of his art in drawing.