THE BASIC ART Sometime between the ages of eighteen and twenty‑four months, children make scribbles that, one day, suddenly became a person. For most people, drawing was their first experience of art—the first realization that a visual design can symbolize something. Lines magically become a different kind of reality. The transformation taking place in the child’s imagination constitutes the very nature of art. In a very personal sense for almost everyone, drawing formed the basis of a lifetime of enjoying art.

Drawing may be considered the basic art for several other reasons. For one, drawings appear among the earliest works of art. For example, the drawings on the walls of the Chauvet Cave (figure 1-1) in southern France date to around 32,000 to 30,000 year ago. They are twice as old as the drawings on the walls of the caves at Altamira in northeast Spain and at Lascaux in southwest France.

1-1 Panel of Horses, ca. 30,000 B.C. Chauvet Cave, France.

In all the prehistoric caves, animals dominate: there are 470 depictions of over a dozen different species at Chauvet Cave. Nothing else seems to have had any importance to the artists other than the animals that once populated the river valley. The one exception at Chauvet is the appearance of the lower torso and legs of a human female. Landscape or a setting of any kind did not exist in the artists’ imagination, although, occasionally, striations in the rock seem to have worked as a ground line. The shape of the rock itself often suggested masses and voids to the cave artist who drew around these suggestive formations on the wall and fit them into the design.

The Chauvet artists used mostly red ochre in the entrance chamber, then turned to black charcoal in the deeper parts of the cave. Artists in other caves used a variety of natural mineral pigments to draw firm outlines in red, black, yellow, brown, and violet directly on the wall. Colors were sometimes heated and mixed. They drew lines with daubs made of a variety of materials or drew them with solid chunks of pigment. No evidence of brushes has been found. To achieve internal coloring, the artist sometimes blew powdered pigment through a hollow bone until the successive circular spots merged into a colored area. The artist who drew a group of four horses at Chauvet stumped the charcoal on the wall to darken the massive heads. Cave artists also made engraved drawings, or petroglyphs, by scraping into the rock with sharp stones. A soft tawny layer coating the walls at Chauvet allowed the artists to draw into it with their fingers.

The animals were all drawn in profile with such a sure sense of proportion that modern observers have no trouble identifying them. The skills of the cave artists betray a high level of artistic ability achieved through unknowable years of earlier practice. No erasures and no pentimenti are visible. Over the thousands of years between Chauvet and Lascaux, the style of representation changed little, and the skills of the Chauvet cave artists are as sophisticated as those of the later artists at Lascaux. Along one segment of the wall at Chauvet, a pack of lions seems to be stalking a herd of bison. Along another segment (figure 1-1), an artist drew four horses behind one another along a diagonal line. The artist scraped the surface of the cave wall around the horse’s heads so that the darkened drawing would stand out more sharply against the light stone. Rather than random, transparent superimpositions as in most other caves, the horses genuinely overlap one another, producing a recession into space. These are not stereotypes of animals but depictions of vigorous life achieved through springy lines and lively poses. The bulging curves of the drawing convey the muscularity of the beasts and their spirited movements. Through careful observation, the prehistoric artists magically unleashed these powerful animals deep in the earth. But after decades of modern speculation, the question “Why?” still remains unanswered.

For the last several centuries, the Western art world has treated drawing as the basic art in another sense. Drawing has been the primary means by which the tradition of art is passed from generation to generation. Whether in centuries‑old academies (figure 1-2) or in contemporary university art studios, education in art usually began with drawing. In the imaginary Spanish Academy—the dream of the French painter Michel-Ange Houasse—advanced students draw from the nude model. In most academies in the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries, before studying the nude, students first copied other drawings or engravings. From the start, they learned how to reproduce a distinct line and a system of internal modeling, which often looked like the lines and hatching of the engraving they had copied.

Despite revolutions in art education, drawing still remains the chief means of instruction because learning to draw sharpens observation, increases perception, and releases self‑expression. Drawing has been singled out as the skill that develops the right side of the brain—the area that handles edges, intervals, and spatial relationships. Low-cost drawing materials can go anywhere and stand ready to use at any time. The ease of making corrections, alterations, and repetitions in drawing encourages experimentation and creativity in the developing artist. In short, drawing has become the chief means for the education of the visual imagination.

1-3 Annibale Carracci, Triumph of Bacchus, 1597-1598. Pen and ink, 16.8 x 22.3 cm. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth.

In many ways, drawing is the basic art form on which all others build. The first creative impulses of a painter or sculptor are commonly expressed in drawings. Painters and sculptors are likely to work out their visual ideas, at least part way, in the less costly and less intractable medium of drawing before tackling their preferred medium. Architects and even photographers are commonly trained to draw, if for no other reason than to train their perceptual skills and develop their creative potential. A spontaneous medium, drawing allows architects and sculptors to visualize possibilities rapidly and to find their way to solutions. Today, even complex computer design programs begin as drawings on the screen. For centuries, most artists prepared for a painting with a campaign of preliminary drawings. They frequently made studies of a model in order to determine the poses of the figures on the canvas. Perhaps the most important study an artist made was the rapid “first thoughts” that tried to visualize the initial inspiration before it cools. These drawings often documented the process of creation (figure 1-3), whereas the finished paintings of most Old Masters usually obliterate all trace of preliminary stages. Preparatory sketches may demonstrate the artist’s striving to perfect the forms, recording his or her sensitive adjustments to them. Since the Renaissance, many collectors have felt that the artist’s awe‑inspiring power of creativity was best preserved in drawings. Consequently, even preliminary working sketches of an artist have been avidly collected and admired.

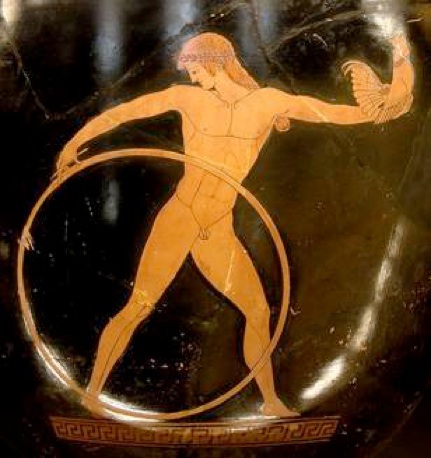

1-4 The Berlin Painter Ganymede, 500-490 B.C. Louvre Museum, Paris.

DEFINITIONS OF DRAWING The art of drawing is hard to define. In most cases, to draw means to make marks on a surface in order to represent something. It usually means to make lines and to close those lines around shapes. Drawings ordinarily begin and often end with contour lines—those imaginary lines around the edges of forms or the boundary lines of any sort of shape. In Western art, the drawing of the human figure on Greek vases (figure 1-4) typifies the use of contour lines. Although the black-painted background of the vase abuts the outer contours of the figure, and the figure is the color of the untouched red clay, every contour is still evident as a flexible and assured line that is simple yet accurate in describing complex anatomy in twisting poses. Continuous and consistent, the lines drawn on Greek vases never thicken or thin. Sparse internal lines may clarify anatomy or depict the folds of cloth, but they do not model the forms in light and dark.

1-5 left. Leonardo da Vinci, detail of Woman’s Face, figure 2-32.

In addition to contour lines, the marks that an artist makes while drawing may also depict values, that is to say, lightness or darkness, and chiaroscuro, or contrasts of light and dark. The art of drawing has established several conventions for their representation. For example, artists in the Renaissance used the closely spaced parallel lines of hatching (figure 1-5) to darken a form.

1-6 Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, detail of Seated River God, figure 3-89.

To produce value contrasts in drawings, especially in the Baroque period, artists often washed diluted ink across the surface (figure 1-6). Over a faint sketch in pen or chalk, the ink wash produced flickering light and dark contrasts and at the same time built solid form.

In the modern period, the artist Georges Seurat made drawings that were almost entirely exercises in value contrasts by rubbing a conté crayon across course textured paper (figure 1-7).

1-7 Georges Seurat, detail of Seated Boy with Straw Hat, figure 4-00

In all these conventions for light and dark, the drawing medium is optically mixed, so to speak, with the lightness of the paper to achieve a certain value. Whether the different values are created by lines, by brushing, or by rubbing, the play of light and dark is a fundamental element in the art of drawing.

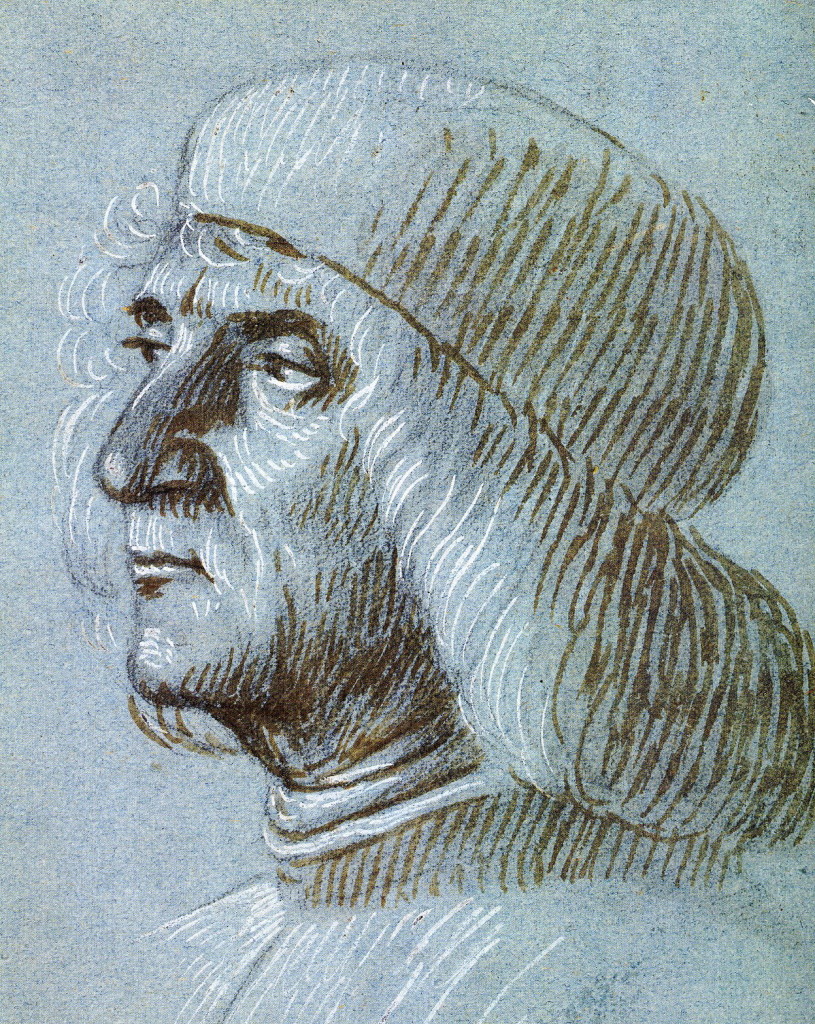

Drawings usually lack color, although Renaissance artists often drew on colored papers (figure 1-8). However, they almost always treated the colored paper as a middle value, rather than as a hue in the spectrum. Traditionally, most drawing media have been limited to black, white, gray, red, and brown, or perhaps a combination of two of them as in figure 1-8. The papers, inks, and natural chalks that artists used in the past varied in color, and even though they may have changed over time, the colors of a drawing are an important aesthetic factor. Yet even when numerous colors were available, most artists tended to use only a limited number of them in any drawing and usually applied areas of color transparently so that the support on which the drawing was made is visible. Full color drawings that fill the entire surface with opaque colors are possible, but not common, and of course they blur the distinction between drawing and painting. Although in normal practice pastel chalks fill the surface with areas of color, the results are normally considered to be drawings.

The art of drawing has occasionally been defined by its subordinate relationship to other media. In this view, true drawings are those made in the preparation of a painting or other larger form of art. A drawing, in other words, is basically a sketch, a trial, and a stage in the invention or elaboration of some grander project. Drawings, therefore, were valued because they recorded an artist’s inspiration and labor for something else. This definition disregarded so-called finished drawings, made for their own sake, which artists have always produced.

DRAWING TOOLS Drawing has often been defined by the tools that are used to make them. If the tool is pencil, the work is a drawing; if the medium is oil colors, it is a painting. (See the Appendix for the history and the characteristics of drawing tools.) Some tools, however, may produce several different kinds of art. For example, artists can use brushes, when dipped in ink, to make drawings as well as to make paintings. In many cases it is only the artist who decides that his or her work is a drawing or a painting.

At different times, artists have preferred one tool over another. Many Renaissance artists liked natural chalk. Modern artists prefer graphite (the pencil). Presumably, the characteristics of the tool suited the style of the artist because different tools seem to determine to some extent what the finished product will look like. Of course, a familiar medium often challenged artists to do something different with it.

Perhaps the essential drawing implement is the artist’s hand. The hand develops the skill to move the tool to create the lines and values that embody the artist’s vision. Popular wisdom believes that drawing skill lies in a person’s ability to draw a straight line. But a ruler makes straight lines better than anyone can freehand. Instead, it is more important that the hand be able to vary a line by moving it around, by speeding up or slowing down, by applying and releasing pressure, by turning and tilting the drawing implement, by knowing when to stop.

THE SUPPORT Although certain tools tend to define what is a drawing, it is just as likely that an artist’s work is called a drawing because of its support. In the past, drawings have been made on wood, cloth, animal skin (including the human body), clay, and stone. Chinese artists, who made little distinction between painting and drawing, frequently drew on expensive silk. In the West in ancient times and throughout the Middle Ages, artists drew on parchment made from the skin of animals such as sheep, goats, or calves, or on vellum, very fine lambskin, kidskin, or calfskin. Parchment must be primed, or rubbed with pumice, ground bone, or chalk to smooth it and to prepare it for drawing. In any age, it is expensive.

Medieval drawings on parchment can be found in books, usually as elaborated illustrations of a sacred text. Most medieval book illustrations are full-colored paintings since the splendor of color was deemed most appropriate for religious works. However, in some manuscripts that were never finished, the uncolored outlines remain visible as drawings. In other books, in which the areas between the lines were only tinted with translucent washes of color, the outline drawings remain the dominant factor, at least until in the thirteenth century when the washes began to model the forms into semblances of three-dimensional objects. Occasionally, reformed monasteries expressed their dedication to the vow of poverty by refusing colored illustrations altogether and illustrated their text with only line drawings. Although artists in the Middle Ages surely made preparatory sketches for book illustrations, metalwork, and glasswork, very few of them remain.

1-9 The Utrecht Psalter, detail Psalm 26, ca. 830. Ink on vellum. University Library, Utrecht,

Almost all medieval drawings are anonymous, but some of them, like the drawings in the outstanding Utrecht Psalter (figure 1-9), have a very personal style. The lines that visualize the psalms throughout this book have a distinctive restlessness about them. Most characteristic are the parallel curves of drapery folds that slash across the twisting, gesticulating figures and jut out as sharp points on some of the figures. Repeated short curves describe the contours of hills that look as wild as those by Dr. Seuss. The tiny figures are clustered in groups in compartments that the rolling landscape provides. They have elongated, tapering legs ending in very springy and thin arched feet. Typically their heads stretch forward from rounded backs in a single line. It would seem that a spirited and imaginative artist, whoever he was, adroitly brandished his pen in spontaneous spasms of inspiration. Nevertheless, experts have identified the hands of as many as eight separate artists who worked on the psalter. And there are indications of faint preliminary pen and stylus work underneath the final, darker lines applied over them.

It is possible that the lines of the Utrecht Psalter were not filled with color in order to give the manuscript an antique look. There are other indications of that intention. For example, the text is lovingly printed in capital letters common in classical time as opposed to the lower case script used in contemporary Carolingian times.

In the Utrecht Psalter, a pen drawing accompanies all 150 psalms and 16 additional canticles and creeds for a total of 166 drawings. Most of the images illustrate the metaphors of the Psalms literally. For instance, the artist illustrates Psalm 26:1, “Dominus inluminatio mea (the Lord is my light),” with a beardless Christ carrying a torch in the porch of a Christian church. From the clouds above, the hand of God sheds rays of light on the psalmist. To illustrate Psalm 26:3, “Si consistant adversus me castra (If armies should encamp against me),” the artist filled the foreground with soldiers who pour out of their tents and charge the psalmist, whom the Lord will protect in his tabernacle (Ps 26:4-6). Some horsemen stumble and fall. In 26:10, the psalmist laments that his father and mother have abandoned him. In the upper right, a man and a woman send a child out of the small house.

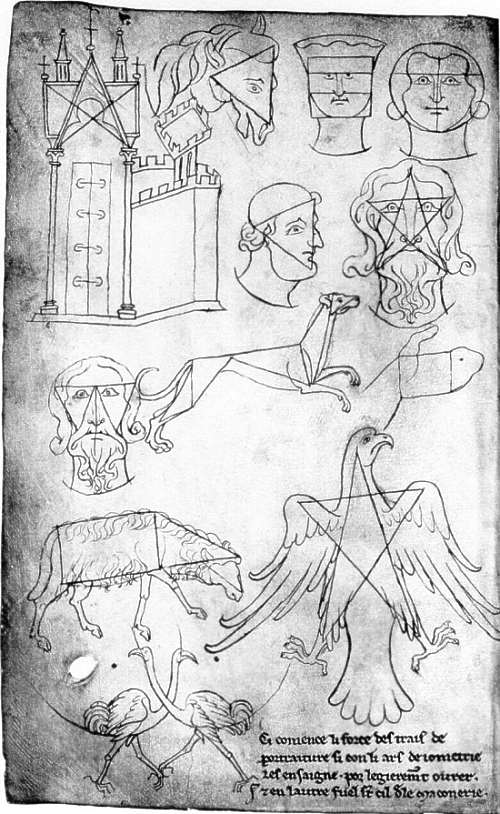

The most famous book of late medieval drawings came from the hand of the inquisitive French draftsman Villard de Honnecourt (figure 1-10). About 1230, he traveled through northern France, making numerous drawings.

1-10 Villard de Honecourt, Portfolio, Plate 36, ca. 1230. Leadpoint and ink on parchment, ca. 24 x 16 cm. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

He often pointedly tells the viewer that the drawings were the results of his observations of the real world. His profession and the function of his drawings remain a mystery, but his volume, like a few other extant collections containing copies of other art works, must have served as a pattern book for artists and architects. Villard’s portfolio contains 250 drawings on 33 leaves of parchment, now stitched together in a pigskin folder. Thirteen to fifteen additional leaves were lost at an early date. He drew animals, the human figure, architecture, church furniture, and mechanical devices, among other items. Despite the presumption of direct observation by Villard, proportions are sometimes determined by underlying geometric shapes.

Different subjects in different scales randomly fill all the available space of the sheet, and the anarchy remained despite his attempt to order the sheets and provide inscriptions. Villard drew in leadpoint, which he then strengthened with dark ink and occasionally with sepia wash. The contour lines he created are unbroken and consistent in width, and thereby somewhat monotonous. His style resembles that of metalworkers around the year 1200—Nicolas of Verdun, for example. Villard’s are finished drawings, very different from true rough sketches such as the trial efforts occasionally found in the margins of contemporary manuscripts.

PAPER Over the last six centuries in the West, artists drew most frequently on paper instead of on animal skins. As a consequence, it might be best to define drawings over that period as “unique works of art on paper.” The statement at first sounds too vague but, on further reflection, it is really quite useful. The word unique in the definition distinguishes drawings from almost all kinds of printmaking, which normally produces multiple impressions on paper. However, the key word in the definition is paper. For until the introduction of paper into the West, drawing, understood as the basic art, led a tenuous existence. Drawing could not come to the fore as the major vehicle for instruction, development, exploration, and creativity, until there was an adequate supply of paper for artists to work with. That event happened in the West in the fifteenth-century, and that is why this survey of the history of drawing begins in that century.

The Chinese invented paper two millennia ago. Their invention traveled through the Islamic world and eventually reached Spain about 1100. Paper mills, beating rags into a mash, were established in Italy by the mid-thirteenth century. In the early fifteenth century, despite improvements in quality, paper was still relatively expensive, although cheaper than parchment. Parchment was not necessarily a better surface for drawing—after all, its surface had to be carefully prepared. Parchment, however, had a reputation for durability—an important consideration when drawings illustrated books or served as models for the members of a workshop and their successors. Then, in the 1450s Guttenberg introduced moveable type and initiated the revolution in book printing. Paper was now in great demand, and its production greatly expanded. Paper became cheaper and more readily available to artists. At the same time, artists began emphasize new functions for drawing and became less concerned about the durability of drawings on paper. A drawing revolution could now begin.

PARAMETERS The history that follows does not attempt to discuss the drawing of every well-known artist. It concentrates instead on the work of drawing enthusiasts—artists who drew constantly, who made drawing a major form of personal expression, who frequently left behind an enormous body of drawn work, and who defined the art of drawing for their times. Despite the great losses of drawn work, especially from earlier centuries, enough remains to indicate who those people were. For better or for worse, there is no canon of the greatest drawings of Western art as there is a generally accepted list of must-see painting, sculpture, and architecture. Necessarily, this history of drawing is often personal. It is a history of drawing, not the history of drawing.

In this history, pastel drawings are included, but not, with some exceptions, watercolors. One reason for the exclusion is that watercolor artists developed brush techniques that take the medium beyond the aims of most drawing. But the major reasons for excluding watercolor are space and time. The history of watercolor demands too much of both. This history does not include architectural drawing for the same reasons.

An attempt has been made to illustrate the drawings in color because black and white photography tends to exaggerate value contrasts in order to make the image visible. Black and white photographs give the impression that all drawings were made with India ink on white paper. The truth is that most pen drawings are in brown ink, and even red chalk drawings come in a variety of shades and intensity.

In the last several decades, historians of art have written extensively about drawings, especially in catalogues of individual artists and catalogues of museum and private collections. The major thrust of this research has been to relate these drawings to the documented paintings or other large-scale works by the artist. This relationship was often essential to determine the authorship and relative date of a drawing. Very often, however, little was written about the evolution of the artist’s style of drawing, about relationships to the work of other draftsmen, or to the development of drawing in general in an age or region. These connections need to be made so that the artistry of the drawing can be appreciated for its own sake.